The Influencer

On Lifestyle as Culture

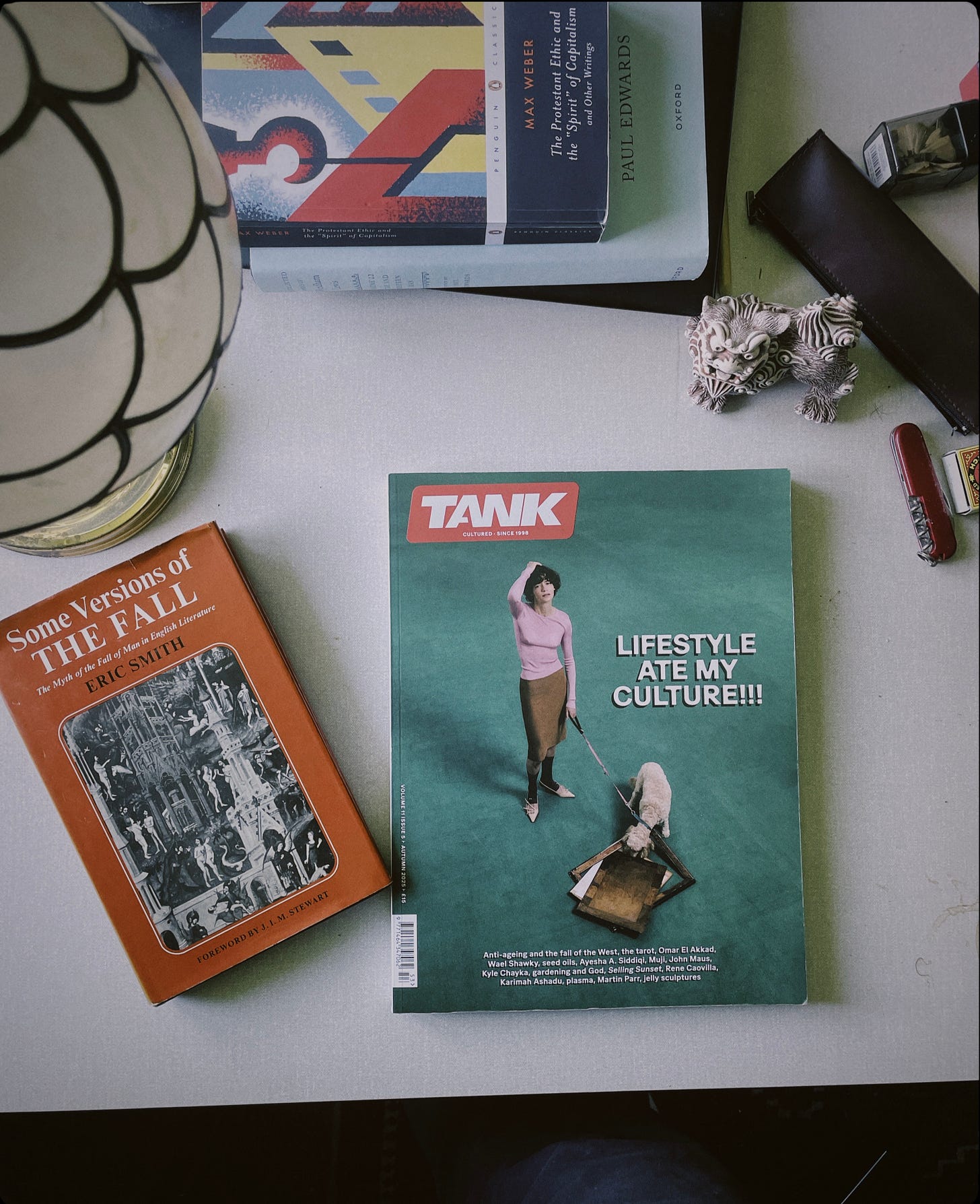

A version of this essay appears in print and online in the current issue of TANK Magazine. Please click on the link to check out all of the wonderful accompanying artwork. The theme of the issue is the subsuming of Culture by Lifestyle, which has many other interesting essays and interviews. You can buy a print copy here. Many thanks to Nell Whittaker for the commission and input, and to Christabel Stewart.

The curious paradox at the heart of the internet lies in its shadowy and bellicose military origins set against the quasi-utopian ideology of its Californian hippie progenitors. A by-product of this dynamic is that the internet has always had an inherently counter-cultural effect: an unmistakable air of informality, which nonetheless never seems completely authentic. At first, we might be confident in our ability to describe what an ‘influencer’ is and what they do – but after some enquiry, it becomes clear that the roles of Influencer and Critic have become indistinct, if not the same.

We might begin with an allusion to three much-cited but vaguely understood cultural theories. The first is the theory of “parasociality”, which derives from a strand of social psychology and anthropology from the 1950s, and has since been used to analyse human relationships in mass media and technology. Another is the theory of “mimetic desire”, originating in Desire, Deceit and the Novel (1961) by the French Catholic literary theorist René Girard. Having spent the majority of his career at Stanford University, Girard’s geographical (and putatively ideological) proximity to Silicon Valley gave him a number of faithful acolytes among the more esoterically inclined tech plutocrats of the 2000s, most notably Peter Thiel. The last theory is not as readily invoked as the other two, yet in my view ought to be accorded equal prominence: the theory of “interpassivity” by the Austrian philosopher Robert Pfaller. In part conceived as a response to “relational art”, this theory originally posited the notion of a delegated enjoyment felt by the spectator towards artworks. However, this relationality is applicable to all other forms of vicarious experience and interaction within the realm of social media and the internet.

All these theories have equal resonance when considering the archetype of the influencer. The relation we feel towards an influencer is indeed parasocial; their common attributes tend to reflect an approachable, self-effacing, and ironic figure devoid of the rarefied otherworldly celebrity that characterised previous eras. The influencer is often an aspirational figure who, on a more abstract level, is also your friend, or at the very least could be given the right conditions. In this way, Girard’s theory of mimetic desire holds that the subject’s desire is always that of the Other; that the fundamental ontological drive does not reside within the self, within individual agency, or indeed through subjectivity – but rather within imitative desire and mimetic rivalry. Yet the influencer is not an object of mimetic rivalry in a straightforward manner, because they often mirror their audience in some crucial aspects; similar in taste, temperament, worldview, and perhaps even appearance. To account for this, Girard offered the notion of “internal mediation” to describe the similarities between model and imitator, who only differ in their lopsided material success. However, by fixating on the influencer’s superiority to their audience, we would ignore the palpable sense of consolation that features heavily in the symbiotic dynamic they share. The audience has a vested interest in preserving the influencer’s success, since this success, always precarious and impermanent, somehow also belongs to them. This vicarious relation, as interpassivity, between influencer and audience, makes the latter a figure of solace, and only nominally a superior model of aspiration. Perhaps then, it can be described more accurately as a process of delegated suffering rather than simply of enjoyment.

Despite the value of these theories, I fear that an overreliance on them obscures a simpler truth about the conditions that have produced The Influencer, who is merely a symptom of a culture that has become synonymous with lifestyle. A fixation with self-help, self-care, and self-optimisation, perhaps inevitably begets auto-fiction, self-portraiture, auto-theory. There are historical antecedents for this tendency, but what seems undeniable in the current moment is that there no longer exists a sharp distinction between artist and critic, performer and spectator, writer and reader, teacher and student, producer and consumer. People go to exhibitions so that they may themselves be artists, read books and write criticism so that they may one day be authors, attend concerts so that they can eventually perform on stage. Such individual aspirations once generally went unfulfilled, and were previously regarded as shameful to admit to unless one possessed the requisite self-belief or some form of acknowledged talent. Failure often manifested in quiet resentment, or achievements upon what Jacques Lacan referred to as the ‘inverted ladder of desire.’ In this vein, perhaps the billionaire philanthropist who endows galleries and museums that bear his name is motivated less by generosity than a sense of regret at having made money instead of art. This dynamic once constituted an underlying truth of the symbiotic relationship between artist and audience, and its transformation in the present moment has made the public forums of cultural exchange into vast classrooms and workshops that also function as group therapy sessions.

The commonly understood social stratifications of “taste” once served as markers of class divisions, famously detailed by Pierre Bourdieu in his seminal 1979 study Distinction. Now, “taste” can no longer reliably be transmitted only through a social habitus produced by historical circumstances or class-based conditioning. For this very reason, within the atomised forums of cultural exchange that now take place almost exclusively on the internet, the most popular “content” often takes the form of advice, recommendations, tips, endorsements – a realm where influencers have attained prominence. This is hardly surprising, given that today there is a sense of profusion, oversaturation and overproduction within all spheres, professions, and in all directions, often exceeding demand. And yet, this departure signals a shift from our previous understanding of “distinction”, where social status was subject to autonomous artistic creation and the material concerns that underpinned it. As Bourdieu noted:

To assert the autonomy of production is to give primacy to that of which the artist is master, i.e., form, manner, style, rather than the “subject”, the external referent, which involves subordination to functions – even if only the most elementary one, that of representing, signifying, saying something […] the shift from an art which imitates nature to an art which imitates art

In this passage, Bourdieu is describing how the habitus of “taste” relied heavily upon the decadent bourgeois ideology of l’art pour l’art. This tendency can be demonstrated by the conditions of a counter-cultural recent past, when artists were more prosperous and “free” to be expressive. To this day, their legacies still serve as universal shibboleths of good artistic taste.

In contrast, the “influencer” is not an artist in that sense that most of us might understand. Their ‘art’, such as it is, is primarily centred on themselves and is not concerned with creation (or production per se) but also – paradoxically - with something more intangible and external to themselves - a ‘potentiality’ they share with an audience composed of others similar to themselves. The distinction is metaphysical, according to the Italian philosopher Julius Evola, a former Dadaist painter and poet turned esoteric fascist mystic. For Evola the signal characteristic of a corrupt modern technological world, hopelessly fallen in his eyes, is its preference for ‘becoming’ over ‘being.’ There is an element of truth within Evola’s insight, despite its disreputable source. Perhaps a world as perpetual “becoming” most accurately describes that inhabited by the influencer, whose “parasocial” and “interpassive” appeal is often to be found in their journey – which matches our own – to becoming something other than themselves. The journey, however, is one without end.

The figure of the influencer clearly pre-dates the internet, and we can see that the same tension between culture and lifestyle are not far from these historical accounts. One of the first truly acrimonious splits within the lively milieu of advanced early 20th-century British artists occurred right before World War I. A central influencer within the Bloomsbury Group, the art critic turned painter Roger Fry established the Omega workshops in 1913 at 33 Fitzroy Square, alongside the painters Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, the sister of Virginia Woolf. It was Fry’s fervent belief that the differences between fine and decorative art were false, and to this end, the Omega workshops' goal was to bring the influence of Post-Impressionism and the rarefied aesthetic ethos of Bloomsbury to the world of interior design, furniture, and textiles. Fry imbued his entrepreneurial scheme with the supposedly benevolent intention of providing younger and poorer artists with a steady income. Impressed with his work Kermesse (1912), a lost painting for which no visual document now exists, Fry engaged the irascible and talented young painter Wyndham Lewis to work at 33 Fitzroy Square.

On the advice of the Daily Mail’s art critic P.G. Konody, the artist Spencer Gore visited the Omega Workshops to discuss a commission for the newspaper’s Ideal Home Exhibition at the Olympia forum in Kensington in 1913. Impressed by their work at the Cave of the Golden Calf cabaret, the organisers wanted Gore and Lewis to provide paintings to decorate the walls of a model room, and for Fry to provide the furniture. Lewis was not present when Gore visited, and the latter left a verbal message regarding details with Fry, who then informed Lewis that his part would only consist of carving a mantelpiece for the fireplace. This puzzled Lewis, since it was not his speciality. Already suspicious, Lewis asked if there were to be any paintings to decorate the walls. Fry denied that there would be. Nevertheless, when Lewis returned from holiday to the workshop, he found a set of large wall paintings for the Ideal Home Exhibition painted by Fry, Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell. Lewis, along with several other disgruntled artists, quit the Omega workshops and founded the Rebel Arts Centre, and subsequently the Vorticist movement – one of the only substantive London-based avant-garde movements of the early 20th century.

For Lewis, the fallout from this incident became the source of a lifelong hatred of the Bloomsbury Group, whose wealthy upper-class members would come to dominate British culture after World War I. It was a conflict which many were able to avoid serving in due to their political connections and powerful protectors, while many of Lewis’s more talented, less moneyed friends and collaborators would die in the trenches. As Lewis wrote bitterly in his first autobiography, Blasting and Bombardiering (1937):

I have always thought that if instead of the really malefic “Bloomsburies”, who with their ambitious and jealous cabal have had such a destructive influence upon the intellectual life of England, something more like the Vienna Café habitués of those days could have been the ones to push themselves into power, that a less sordid atmosphere would have prevailed. The writing and painting world of London might have been less like the afternoon tea-party of a perverse spinster.

But “they had money” and “we hadn’t”, Lewis recalled bitterly. Although his antipathy was undoubtedly underpinned by an objection to their wealth and influence – they were in a sense the original “nepo babies” – it is clear that these material complaints underpinned other aesthetic objections. As Bourdieu maintained, the Post-Impressionism which Roger Fry championed was the “product of an artistic intention which asserts the primacy of the mode of representation over the object of representation, demands categorically an attention to form which previous art only demanded conditionally.”

An attention to “form” was arguably something that Lewis and Fry shared, but their attitudes towards it diverged significantly. The occasion of their split – the Ideal Home Exhibition – is noteworthy in defining this opposition. First staged in 1908 at a time when 90% of the British Public rented their homes, the Daily Mail’s owner Lord Northcliffe conceived of the exhibition to encourage discourse over better housing conditions for everyone. However, it quickly became a forum for expensive design, luxury interiors and products catering to the wealthy. Fry likely thought nothing of taking such a commission away from an impecunious and déclassé artist such as Lewis, since the ethos and principles of the exhibition predominantly matched his own. For Lewis, form was an essential philosophical category that could never receive proper expression in any sort of consumer product. This much was clear in the acerbic letter he circulated on leaving Fry’s Omega workshop:

As to its tendencies in Art, they alone would be sufficient to make it very difficult for any vigorous art-instincts to long remain under that roof. The Idol is still Prettiness, with its mid-Victorian languish of the neck […] despite the Post-What-Not fashionableness of its draperies. This family of strayed and Dissenting Aesthetes, however, were compelled to call in as much modern talent as they could find, to do the rough and masculine work without which they knew their efforts would not rise above the level of a pleasant tea-party or command more attention.

Evident in his fondness for the “tea-party” analogy vis-à-vis Bloomsbury, it’s clear that Lewis thought poorly of the commercial aestheticism of Fry. Indeed, its de haut en bas pose of supposed dissent and radicalism was also amply reflected in the queer and liberated promiscuity of the Bloomsbury group, which was insulated from the legal and societal constraints imposed on sexuality within wider society. Lewis found all of this to be anathema to the vitalist masculine impulses that he admired most within the artistic avant-garde of Europe. Yet beyond these reflexively antagonistic, homophobic and petty criticisms, something more important was signified by this debacle that returns us to the material interests of class. As Professor Paul Edwards concisely observed in his seminal study Wyndham Lewis: Painter and Writer (2000): “For Lewis, the episode became paradigmatic of the problem of the economics and politics of Art in England, where moneyed people who should have been patrons competed as “artists” themselves with the professionals who depended on them.” As with the Ideal Home fiasco, the embryonic forms of the issues that now define the age of the influencer, are situated within the transposable domains of culture and lifestyle.

No other contemporary art critic channels the OG influencer spirit of Roger Fry more than Dean Kissick, who clearly possesses significant publicist instincts on a par with Serge Diaghilev, F.T Marinetti, and Warhol – even if they are somewhat tempered by the requisite demands of relatability and internet parasociality. My objection to Kissick’s viral Harper’s essay “The Painted Protest” (2024) – a rather anodyne “anti-woke” intervention into contemporary art discourse – was not due to my attachment to vagaries of “wokeness” or tedious political art in general. In our theory of the Ideological Aesthetic (2023), art historian Christos Asomatos and I suggested that in the present moment the domains of the ideological and the aesthetic often dissolve into one another, becoming interchangeable, mutually constitutive and dialectically related. Such a phenomenon thrives under the conditions that produced “woke art”, namely, a social field defined by technological excess, characterised by a cumulative state of hyper-politicisation which results in a state of effective depoliticisation. Within this paradigm, political art can only be made in terms of an institutionalised oppositionality, a form of antagonism that focuses on the free expression that makes it possible, whilst simultaneously rendering that same freedom inconsequential. To forge an interesting position on this dynamic would require a willingness to engage in an honest and immanent critique. Kissick’s refusal to do so reveals that he is less motivated by his purported function as an earnest art critic, rather than by his other, more authentic role as influencer, as a trend-setter – a cultural factotum of taste.

Of course, Kissick’s salvo against the identitarian artworld is unconvincing in no small part because he once passionately championed the same aesthetics of cloying familiarity he now apparently bemoans. Yet the most risible facet of the essay was its middling attempt at “artful” auto-expression, its dubious self-portrait of the sympathetic critic as artist, its reflexive recourse to the subjectivity of the trite personal essay format, and the faux solemnity of its appeal to some sense of collective fatigue among his parasocially inclined audience. But what remains most exasperating is its clear kinship with the pretty and fashionable draperies, Victorian languish, and instrumentalised aesthetics of the duplicitous Roger Fry. When Kissick bemoans the loss of the art world of a decade ago, his nostalgic lament seems to be principally for the loss of a lifestyle rather than culture. By my recollection, the lost world he mourns was just as aesthetically unimaginative, trite and awful ten years ago as it is now. It is one of the most incomprehensible oddities of contemporary nostalgia that the yearning for phantom wounds becomes more bizarre, that the time periods become more short-lived; the objects of longing more puzzling. Nostalgia, generally, is less a longing for an object than it is for a fleeting state of being, mostly for that of youth. But for the youth today, forced to perceive culture in terms of lifestyle, object and being are interchangeable. By acquiring the product, they hope, in vain, to acquire the spirit in which it was created.

In this way, Kissick’s argument has much in common with the current appetite for the most forgettable and derisory aspects of early to mid-2000s music, which have now been re-branded as “indie-sleaze”. Perhaps in a few years from now, this bizarre nostalgia might even evolve to become a yearning for the fashions and questionable music of “posh-wave” bands like Mumford and Sons. A horrifying prospect! But if there is money to be made, or blood to be drawn from the desiccated stone of recent lifestyle-culture, those who only serve the cannibalistic imperatives of our present economic system will happily oblige the whims of the highest bidder. It seems that in the contemporary moment, lifestyle as an “art of living”, has replaced both “art” and “living”, leaving in their place a disparate collection of objects and products from which we can only try to forge some semblance of culture. Yet no sense of inevitability should attach to this moment, because the conditions which have produced it are not immutable. If we can break free from our overreliance on the pseudo-reality provided to us by rapacious technological Semio-corporations, the influence of which seeps into every aspect of the spiritually impoverished present, the spell of the Influencer can be broken.

The earliest forms of cultural expression, such as cave paintings, were not far removed from a state of ‘nature.’ They served intangible ritualistic functions which we still don’t quite comprehend. Yet we do understand, instinctively, that they existed on a completely different plane from the instrumentalised demands of the art ‘market’, from branding, publicity, advertising, and all other forms of confected influence that have come with the catabolic and fundamentally destructive economic system we are forced to inhabit. Clearly, the Influencer is not a completely neutral figure within this paradigm, but neither are they an entirely nefarious one. Rather, the centrality afforded to this figure – merely a version of ourselves, after all - and the amorphous guidance they provide to those otherwise adrift in a sea of lifestyle content, should inform us that the influencer is a symptom of an impending shift in contemporary aesthetic production and consumption. The outcome of this shift is still to be determined. Teetering on the precipice, below a raging deluge of AI slop and de-personalised affectless art, more and more people are starting to agree that the elusive secrets behind those ‘aurochs and angels’, painted in durable pigments for mysterious reasons, might indeed be the most important of them all, and that it ought to be our duty to attempt to fathom them.

Oh my goodness, did I enjoy this. I just stumbled upon you the other day and am so glad I did. I. have not seen writing on Substack sharper than yours, and your topic and development of it is fantastic. I think about these matters a lot. The children up and down my block all say they want to be influencers, and I'm putting a cultural product on Substack. I have no desire to be an influencer, but your essay makes me wonder, what does it even mean to say that? I am not able to write in this mode in the way you can and feel inadequate to really engage on the substance of what you're saying, but I was stopped cold by the cave painting part. This is something I think about a lot. My writing is a little unusual, and I've had trouble getting an agent. I joined Substack a couple of weeks ago to put my fiction into the world, and as people have started to read it, I've found myself wondering more intensely than ever: exactly why do I do this? A few days ago I came upon the image of the cave painter. He/She wasn't trying to get thousands of likes. They just wanted to get something figured out in "media," and then maybe show it to the other people in the cave. I so appreciated your bringing this up. Looking forward to reading more. -- Andrew