The E-Girl

On a contemporary tragic archetype

‘I find woman more bitter than death; she is a snare, her heart a net, her arms are chains. He who is pleasing to God eludes her, but the sinner is her captive.’

– Ecclesiastes, quoted in a letter from Heloise to Abelard.

My previous short essay on the ‘Internet Guy’ was well received, so I’ve decided to make a little series where I consider some other internet archetypes. I may at some point expand this into something more boring, formal and considered but for the moment, as a caveat, I must stress that I am only shooting from the hip.

This entry is bound to be particularly vexing to some because I’m not at all well-versed in the genealogy of the E-Girl. I don’t think I’m ‘online’ enough to be overly familiar with many actual E-girls, so this is simply a collection of abstract thoughts. I spent a regrettable amount of time on internet forums and social media for my novel AGONIST, and this aesthetic ‘research’ will serve as the basis of these disparate impressions. In this vein, I also have some familiarity with the Dasha Nekrasova who appears to be the E-Girl avant la lettre, serving as the model for those who have come in her wake. Though not about her specifically, perhaps it’s her unwieldy, but essentially benign, influence that will be most keenly felt in these impressions, which I hope are applicable more generally.

My most ‘successful’ academic article by citation, among a very meagre offering, is one I published in a Norwegian cultural anthropology journal in 2017 about Angela Nagle’s book Kill All Normies, masculinity and Internet Culture Wars. Rather puzzlingly, it’s been cited by various sociologists, legal scholars and politicians, and I still receive occasional but effusive emails asking me to elaborate on certain points. In thinking about the E-Girl, some points that I brought up in that article come to mind. The E-Girl seems to have emerged from the ashes of Gamergate, the watershed moment for internet culture, a mass hysteria event occasioned by the unwelcome intrusion of a banal écriture feminine into the heretofore undisturbed fantasy world of the male gamer. The E-Girl, then, is borne of a consoling male desire, a fantasy projection without a doubt, but not an entirely uncharitable one: it is an attempt at mediation with an emergent feminized culture.

When speaking of the ‘internet guy’ I speculated about the role of Robert Pfaller’s theory of ‘interpassivity’, and the notion of delegated enjoyment, wherein the ‘internet guy’ is related to a wider shift from identification and mimetic aspiration to consolation, i.e that these are not people one aspires to be, but rather who one already is - neither loved completely nor despised entirely. My sense is this applies also to the E-girl, since her audience is mostly composed of male admirers. She is not exactly the unattainable fantasy (as all fantasies once were), the ideal girlfriend, but rather one who is felt to be deserved, a consolatory presence not entirely outwith the realms of possibility. This relation, however, is not one of delegated enjoyment, but rather one of delegated suffering.

It is a truism that American Culture is Global culture, and every innocuous and tedious aspect of it eventually finds an echo in the far-off regions of its vast imperium. One is the infantile psychodrama of High School as the central determining factor of one’s place within the contemporary American Kulturkampf. It is well to note, however, that the E-Girl is not in the same genre as the perennial Hollywood archetypes of the Cheerleader or Homecoming Queen, though her motivations seem to be in studied opposition to them. Mainstream culture is now the culture of the outsider, the maladroit, the malcontent, the malefactor. (I need not belabour the psychological infantilism that underpins contemporary culture, but I have written about it a couple of years back). Her affect is counter-cultural, her beauty irregular yet emphatic (jolie laide), her manner approachable and self-effacing, her interests, humour and modes of expression distinctly un-feminine (even uncouth), but most importantly, she seemingly thrives on male approval and attention. Much like the ‘internet guy’, the E-Girl is a putative ‘outsider’ in a modern world where, to paraphrase Louis Althusser, there remains ‘nothing but outside.’ The E-girl is not strictly an object of para-social or mimetic desire, but is, nonetheless, essentially a sympathetic figure, because she is in the final analysis a tragic one.

Contemporary culture is as fixated on suicide as it is afraid of death. How else does one explain such stultifying lives, which are mere dreams of death. It is a particularly galling stratagem to look to literary history for facile prototypes and easy coincidences, but the strange historical (hysterical) phenomenon Wertherfieber (after Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther) is to some extent apt. As Emile Durkheim noted, suicide is mostly absent in societies subject to extreme poverty and deprivation – and more common in richer, more developed ones where the forces of technological and cultural anomie run rampant. Considered this way it is no mistake that Wertherfieber, the first wave of mass copycat-suicide occasioned by a work of mass fiction, took place just as Germany was beginning to emerge as the pre-eminent industrial and intellectual powerhouse of Europe. Wyndham Lewis thought it to do with the fatalistic nature of the Teutonic national temperament:

Goethe, with a book, set free the Weltschmerzen of the suicidal Teuton. The razors flashed all over the Teuton world. The pistol-smoke went up from every village. He had pressed a nerve of a definite type of Teutonic man, and made a small desperate sub-race suddenly active.

Yet a fixation on the Sturm und Drang national character is somewhat misguided, as is any characterisation of Goethe’s tale as only one of romantic heroism, wherein the tragic figure takes it upon himself to solve an impossible love triangle by violently removing himself from the equation. The murder-suicide of the poet Heinrich von Kleist and Henriette Vogel is perhaps an instructive counter-example. Christine Friedel’s 2014 film Amour Fou is a psychologically incisive treatment of the topic. In the film, the poet is an ungainly, awkward character – in many ways unheroic, even somewhat repulsive and cowardly. When his plan for a murder-suicide is rejected by his original target, his pretty cousin Marie, he immediately attempts to convince the plain and awkward Henriette to follow him by casually declaring her life to be unpleasant and useless, and telling her that she is unloved because she is also an outsider. Initially, she too rebuffs him, declaring that she has a husband and child to live for. Later, on finding out that she might be dying of cancer, she reconsiders his offer. The poet is, however, at first unmoved. He desires a woman who wants to die for him, not for her own reasons; he wants the tragedy of unattainable ‘love’, the intensity of obsession, and a reciprocated burning desire for mutual death. Hope is rekindled by Henriette’s husband, who is seeking a second opinion on her terminal illness, causing her to have doubts about Kleist’s plan. But having been rejected again by Marie, Heinrich wishes to carry out the act as soon as possible. He asks Henriette to come on a walk with him where he suddenly shoots her, before killing himself. The relevance of this psychological portrait to the paradigm of the E-Girl is self-evident. She is a somewhat willing (morbid) projection of a subjective, wilful, masculine insufficiency, and is thus a co-dependent, symbiotic character. The E-Girl is constituted, and sustained, by the ‘Internet Guy.’ The relation is ultimately a platonic one, and if occasionally onanistic, on the whole chaste.

There is a distinctly theological texture to the phenomenon of the E-Girl, one which she readily acknowledges, reproducing it through performative piety, and various semiotic and aesthetic expressions. This self-conscious nod to religious iconography reconfirms the essentially tragic nature of the E-Girl, but we would be mistaken in reaching for the most obvious Christian analogues; the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, or even Joan of Arc. Like much else on the internet, things that seemingly allude to perennial traditions are more modern in quality, the product of a secular theology as opposed to a spiritual one.

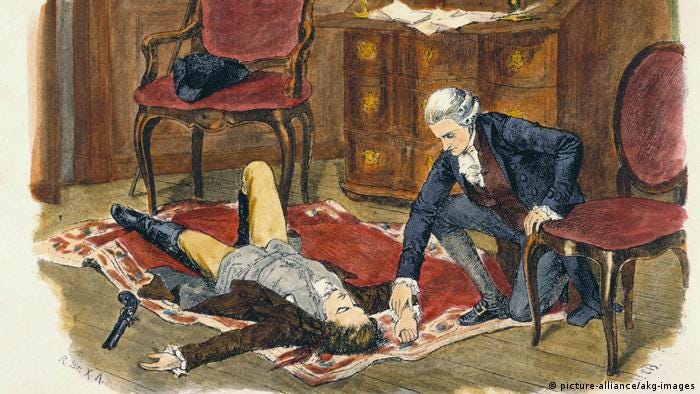

In looking for an appropriate model, one that reflects the Kleistian desire for a willing and pliant victim of masculine angst and insufficiency, the tale of Abelard and Heloise seems the most appropriate. The medieval tragedy of the famed logician Peter Abelard and his lover, and erstwhile pupil, Heloise is beautifully recounted through their letters, and in his autobiography Historia Calamitatum. The arrogant upstart Abelard seduces the teenage ingénue Heloise, and they engage in a passionate sexual relationship which results in her pregnancy. After having her give birth to their son away from public scrutiny at his ancestral home, Abelard is repeatedly confronted by Heloise’s powerful uncle to marry her, which he does – but only in secret – despite Heloise’s protestations that she prefers to be his ‘whore’ rather than his ‘wife.’ For unknown reasons, and perhaps with a mind to make amends before God, Abelard removes Heloise from her uncle’s house and makes her take vows and join a convent. In revenge for this, her uncle has his servants break into Abelard’s chambers and violently castrate him. Ashamed, broken, disfigured and alone – he enters a monastery, from where he later takes up the famous correspondence with Heloise.

These letters underpin the European literary romantic tradition, and without them, the epistolary tragedy of Goethe, and countless others, simply would not exist. However, in focusing on the masculine anguish of Abelard, we tend to discount the poignant and thoroughly modern agency eloquently expressed by Heloise, whose carnal obsession remains profane and far from divine, despite herself: ‘How can it be called repentance for sins, however great the mortification of the flesh, if the mind still retains the will to sin and is on fire with its old desires?’

It is, however, within Heloise’s undying devotion to her now estranged, maimed and castrated husband – ‘my only love’- that we find a distant echo of a tendency now clearly apparent within the modern tragic figure of the E-Girl:

At every stage of my life up to now, as God knows, I have feared to offend you rather than God, and tried to please you more than him. It was your command, not love of God which made me take the veil.

[…] To me your praise is the more dangerous because I welcome it. The more anxious I am to please you in everything, the more I am won over and delighted by it. I beg you, be fearful for me always, instead of feeling confidence in me, so that I may always find help in your solicitude.

It is not Heloise’s yearning for the carnal pleasures that she once shared but their memories – or to put it in terms more conducive to our moment, their ‘simulation’ - that speaks most to our present subject. A frequently mistaken critique of the male psyche holds that what men truly desire is a beautiful, silent, compliant, and dutiful woman. I have yet to meet any man who seriously entertained such notions. On the contrary, I have known countless men, myself included, who have been hopelessly in love with vociferous, strong-willed women who lead chaotic lives eliciting their sympathy and desire to protect; women capable of great cruelty but equally of intense devotion which, most importantly perhaps, is freely given.

For his part, Abelard would belatedly come to recognise the true depth of Heloise’s feeling:

[she]…argued that the name of mistress instead of wife would be dearer to her and more honourable for me – only love freely given should keep me for her, not the constriction of a marriage tie, and if we had been parted for a time, we should find the joy of being together all the sweeter the rarer our meetings were. But at last she saw that her attempts to persuade or dissuade me were making no impression on my foolish obstinancy, and she could not bear to offend me; so amidst her deep sighs and tears she ended in these words: ‘We shall both be destroyed. All that is left us is suffering as great as our love has been.’ In this, the whole world knows, she has shown herself a true prophet.

In his last work of criticism, The Dear Purchase, published shortly before his death, Professor J.P Stern wrote about a recurring theme in various works of German modernist literature which had preoccupied him for over thirty years. The term ‘dear’ used to connote expensive is common to variants of British English, and Stern meant by this the high price one has to pay to purchase salvation:

Beyond the dualisms of spiritual and temporal, worldly and transcendent, in the much frequented no-man’s land between finite and infinite, each of these authors express the living experience of a salvation or validation of man which is to be attained at the highest price that man can conceive of: while at times the price exacted is beyond – tantalizingly just beyond – what man can pay with his entire being and existence. It is a salvation whose very validity is relative to its being supremely difficult of attainment, or even…to its unattainableness.

Stern’s ‘dear’ purchase was not, he maintained, a Christian notion of salvation but a secular one – and though his discussions are of modern writers, we cannot fail to see almost the entire history of love and literature as one of heavy prices paid, and tragic costs exacted. Indeed, did Abelard not pay a high price for his reckless masculine will through being brutally emasculated? In stark contrast, preferring to luxuriate in suffering and entropy, the castration of the ‘Internet Guy’ is merely symbolic, though this hardly diminishes its potency.

The Internet Guy/E-girl dyad thus attains a certain pathos, peculiarly tragic in a decidedly contemporary way. It attempts to approximate and simulate the suicidal Amour Fou of a bygone era, but in being fundamentally a virtual relation - and thus with the vital elements of risk and danger removed - it is a desire that is fated to never be consummated. She is an echo, a projection of Narcissus, not only of his chaste, plausible and attainable desire but above all else his consolation, the spectral manifestation of a price he is unable, and unwilling, to pay.

great writing, great references, + you saw right through this ‘relationship’. woahh i loved reading it!

this is such an athletic intellectual exploration of the E-Girl and i love it