Simp Lit

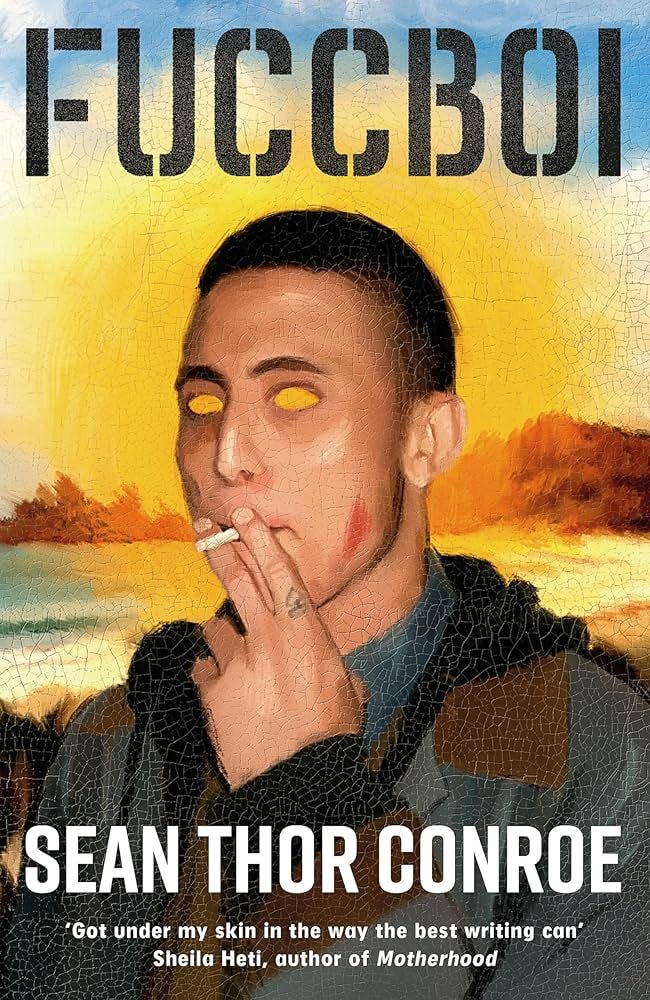

Review of Fuccboi (2022) by Sean Thor Conroe

I wanted as far as possible to approach this novel on its own terms, to provide an account of its formal and literary qualities, but I soon realised this wasn’t possible in any meaningful way. I also didn’t want to give too much consideration to its purported ‘message’', or ideological content, which are embellished impositions that I doubt the author h…