*My own pictures from the exhibition can be found at the end of this piece.

A couple of months ago I went to see the Günter Brus exhibition, planned during his lifetime, at the Kunsthaus Bregenz. Since he died in February this year at 85 years old, the exhibition was something of a retrospective. I found myself deeply affected in a way that I rarely am by art exhibits, and I’m still not quite sure why. There were many images I was drawn to when I was younger, for no apparent reason other than they looked cool. In retrospect, with a characteristic mix of curiosity and indolence, I possibly sensed that those images were of the utmost importance but also that it wouldn’t do to think about them too much. I can’t discount a conscious tendency to be avoidant, but I suspect it was most likely laziness.

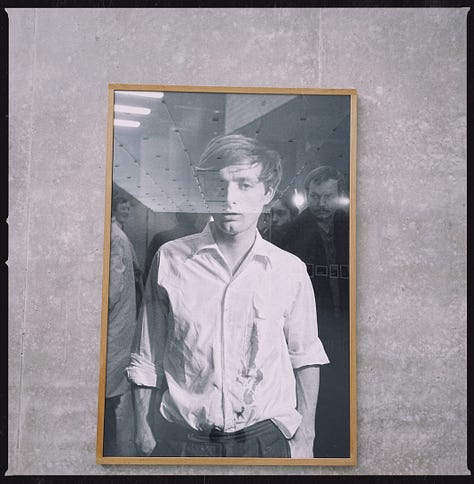

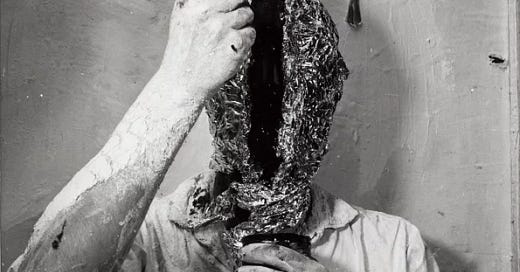

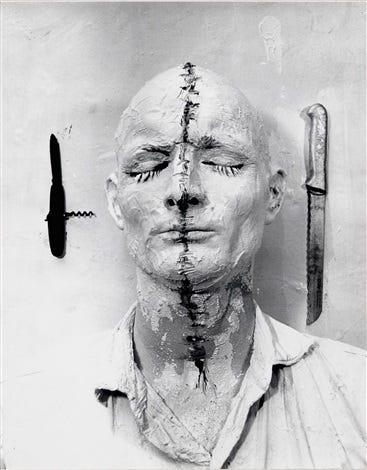

Among these images was one I saw in 2007 in the art history section of the university library, a still from Günter Brus’s performance Selbstmalung (Self-painting) from 1964. A couple of years later I saw Brus’s fellow actionist Herman Nitsch perform an organ composition at the University of Glasgow chapel. The Brus image would adorn the flyer for a sparsely attended post-punk night I briefly DJ’d in Manchester in 2009, and in retrospect seems also to have heavily influenced a music video made for my band Un Cadavre in 2011. Francis Bacon was fixated on the macabre image of the wounded nurse in pince-nez from the famous Odessa steps massacre scene in Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, and there would be many overt and occluded references to it in his paintings. I could attempt to explain my fascination in these terms, but my fixations have never occasioned an exhaustive need to understand the context. I did eventually read more about Actionism later when I lived in Vienna, occasioned in 2016 by a rather quaint performance at the KunstGarten in Graz by an elderly Heinz Cibulka, a frequent collaborator of Nitsch and Rudolf Schwarzkogler. He was quietly and serenely making compost to a soundtrack of his voice reading his weekly shopping list. I remember feeling quite keenly the dissonance between that performance, and those of blood and gore I had seen in various books and videos.

In attempting some cursory background reading on Brus, I came across an article on his 2018 exhibition Unrest after the Storm at the 21er Haus in Vienna, written by noted Austrian journalist Robert Sommer. Sommer writes in admiration of Brus’s controversial yet successful international career, decried by authorities and tabloids at the time as a national ‘disgrace’, his legal troubles and eventual rehabilitation and successful integration into the Austrian cultural scene, and how his legacy can now inspire new generations of artists to also be a ‘disgrace.’ The article ends on a distinctly ideological note:

Die schwarzblaue Macht hat böse Kunst und böse Kunstschaffende verdient

(The Black/Blue Power warrants ‘bad’ art and ‘bad’ artists)

The invocation of Black/Blue Power referring to the alliance of the Austrian Conservative Party and the far-right People’s Party is, of course, noteworthy in signalling the writer’s political leanings. More interesting here is the valorisation of the terms ‘bad’ (or ‘evil') art and ‘bad artist’ as things which stand in opposition to those right-wing or reactionary powers. This suggests another dimension to this appraisal.

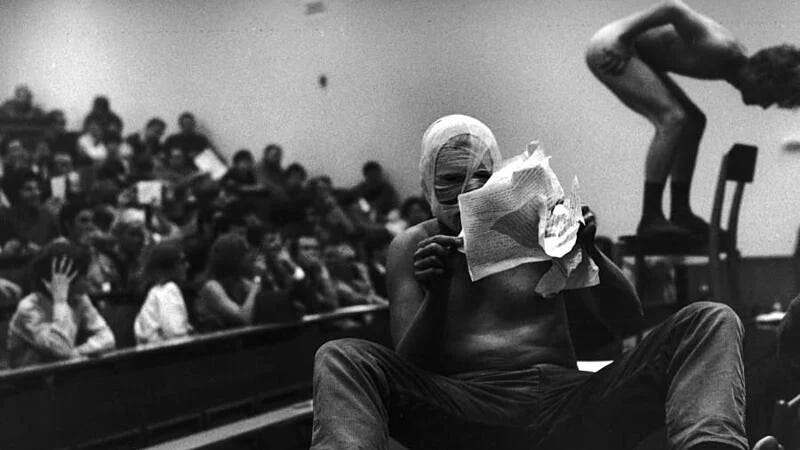

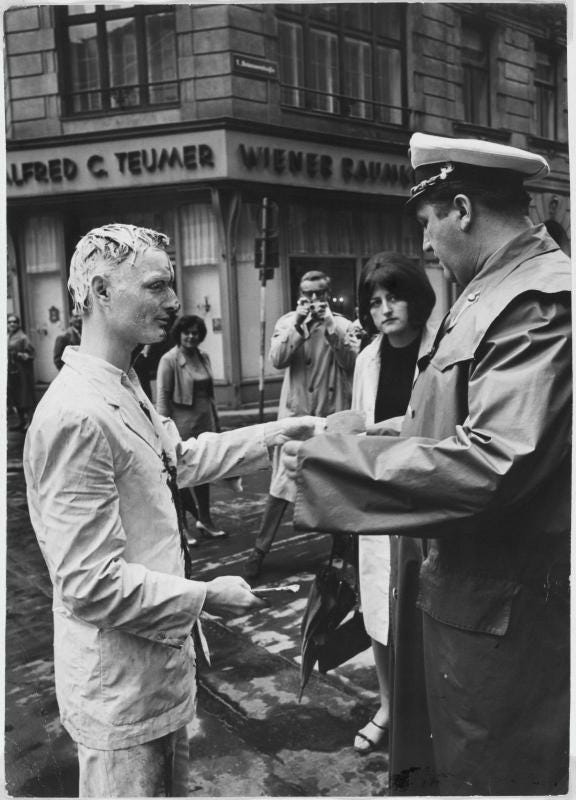

The official narrative of Gunter Brus is a good example of the 68 generation’s careful curation of their legacy, which inevitably tends toward the heroic and hagiographic. In the case of Brus, he was arrested and forced into exile for his role in the ‘Art and Revolution’ performance at the University of Vienna in 1968, where he mutilated himself, drank his urine, vomited and defecated on the Austrian flag, and smeared faeces all over himself while singing the national anthem. The ostensible purpose was to highlight the country’s hypocrisy and state-sanctioned repression; its disinclination to confront its enthusiastic role in the sadism of the Nazi era, preferring the absurd narrative of victimhood and foreign occupation. In the aftermath of the Art and Revolution performance, Brus was sentenced to 6 months in prison for obscenity and defaming state symbols, causing him to flee to West Berlin for many years. He returned in the seventies after his conviction was commuted to a fine. He was eventually awarded the Grand Austrian State Prize in 1996. There appear to be few types of work historically within the ‘transgressive’ mode that are not subject to eventual cultural recuperation by the bourgeois liberal cultural state apparatuses.

Rebellion in that era was governed by a certain determinism that seems, in retrospect, to have been almost utopian in its simplicity. The enemies were clear: your parents, the family, and all of the paternalistic repressive state and religious apparatuses which upheld them. The evidence of their complicity in the horrors which they had clearly condoned, accepted, or simply ignored during the War was incontrovertible. As a result, much of 1960s counter-cultural thought was predicated upon a philosophical formalisation of a certain inversion of Christian ideological ‘interpellation.’ In this vein, it’s somewhat important for us to bear in mind that Louis Althusser’s theory of ideology is in many ways a document of the 1960s counter-culture, composed amid the upheavals of May 68 and published at the close of the decade. The process by which an individual is interpellated by ideology was famously framed by Althusser as equivalent to being accosted in the street by a Policeman (the original French word interpellé is often translated as ‘arrested’). The ideological interpellation of the Christian ‘Good Subject’ occurs, according to Althusser, in four stages. In the first instance, there is the interpellation of the individual as a subject, and in the second their subjection to the Subject (note the capital letter, by which Althusser signifies God in the Christian Church). Thirdly, there is the “mutual recognition of subjects and Subject, the subjects’ recognition of each other, and, finally, the subject’s recognition of himself.’ Good subjects, Althusser notes, function ‘all by themselves’ through positioning themselves within an extant status quo:

They must be obedient to God, to their conscience, to the priest, to de Gaulle, to the boss, to the engineer, that thou shalt ‘love thy neighbour as thyself’, etc. Their concrete material behaviour is simply the inscription in life of the admirable words of the prayer: ‘Amen – So Be it’.

This chain of interpellation ends with the “absolute guarantee” of these conditions, which takes the form of the invocation of the word ‘Amen’ customarily found after Christian prayers, which can be literally translated as ‘so be it.’ In contrast to the normative ‘Good’ Christian subject, Althusser maintains, the ‘Bad’ subject is an exception to the functioning of this ideological interpellation who “provokes the intervention of one of the detachments of the (repressive) State Apparatus” (IISA 55). The implication is that this ‘bad’ subject is defined by their rebellion against the authority of the Church by deviating from its law (as a heretic, as a sinner, or an apostate).

As we can observe, the description and function which Althusser provides of this ‘bad’ subject can be imposed upon an artist of the 1960s counter-cultural type, such as Gunter Brus, with little effort or any straining of its definitional boundaries. For the counter-cultural ‘Bad subject’, rebellion against the ‘Good’ normative functioning of ideological interpellation was an end in and of itself, achieved through a simple devotion to autonomous self-actualisation at its most mild, or indeed a complete rejection, degradation or iconoclastic destruction of the symbols of the repressive order at its most pronounced. Again, it must be acknowledged that the motivations behind this rebellious desire are self-evident to the ‘bad subject’, who had observed how familiar and familial unifying structures (‘nation’, ‘church’, ‘race’) had wrought untold horror and depravity. But in rejecting, discrediting or dismantling all such systems wholesale in favour of one which championed the individual ego, the bad subject unintentionally rejected all possibilities for ‘organic solidarity’, which at its fundamental level, provides the requisite constraints and boundaries required for functional societies capable of reproducing themselves

This institutionalisation (and normalisation) of oppositionality is central to our understanding of the present, where it has become one of the main ways for many to guarantee an ‘authentic’ sense of self. The internet is, and remains, a totalising counter-cultural force, one which renders all subjects ‘bad subjects.’ The effects have been slow-burning, but the violent cultural ruptures of the 1960s were equally as effective as other overtly violent revolutions in radically changing society - mostly in ways which can be felt in our present moment. To take one example, the unwieldy philosophical influence of Michel Foucault – himself an exemplary Catholic Bad Subject – provided an epistemology of the repressed histories of the bad subject with the intended goal of effecting a qualitative inversion of the very categories of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ within the collective consciousness. This endeavour was largely successful, as the contemporary moment is indeed one defined by the primacy of the Bad Subject and their effective universalisation. Their heretofore ‘trangressive’ tendencies have effectively been recuperated within the neoliberal ideological state apparatuses and reflected back to them through the cultural super-structure. The ideological state is parasitic upon culture, yet it is only capable of acting technocratically, responding to ‘material’ conditions, vis a vis a present where the notion of the ideological and the aesthetic are co-constitutive, co-dependent and interchangeable. We appear to exist amidst an atmosphere of seeming hyper-politicisation that has, paradoxically, led to a concomitant state of de-politicisation that renders ideology aesthetic, and the aesthetic ideological.

The above theoretical tangent does little to explain my reaction to that Brus exhibition, which I have little hesitation in admitting was very much admiring. There are many artists of that generation which we can compare to Brus, each equally ‘bad’ in their own way. We can observe a certain trajectory as they matured, once the ideological state apparatuses which they had positioned themselves against in defining their ‘badness’ were replaced by ones which served and complimented them, often peopled by fellow ‘bad subjects’ who had taken a long march through the institutions, and eventually captured them. In some of these artists and thinkers, once the shift occurred, often all that was left was an unflattering and megalomaniacal narcissism. Indeed, the later biography of Brus’s fellow Actionist Otto Muehl is a disturbing illustration of this tendency. Rejecting art in favour of founding a radical commune and cult centred on his political views (the rejection of parental attachment, monogamy and marriage etc) - Muehl would eventually come to see himself as a living God, and was later convicted and served seven years in prison for paedophilic rape and sexual abuse.

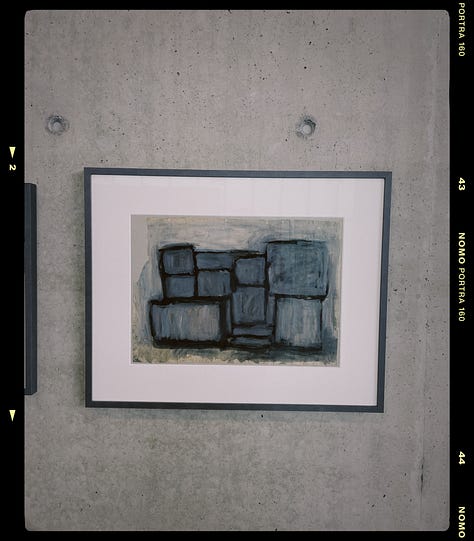

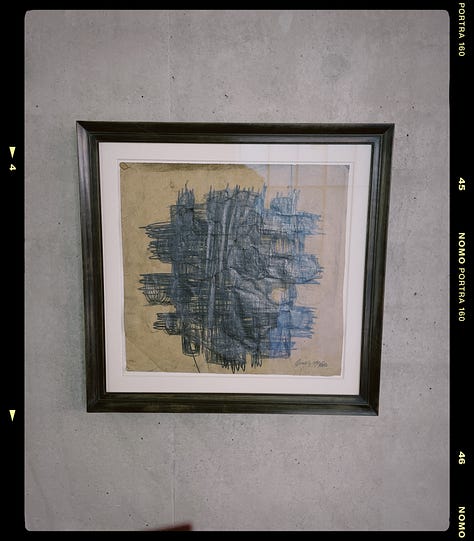

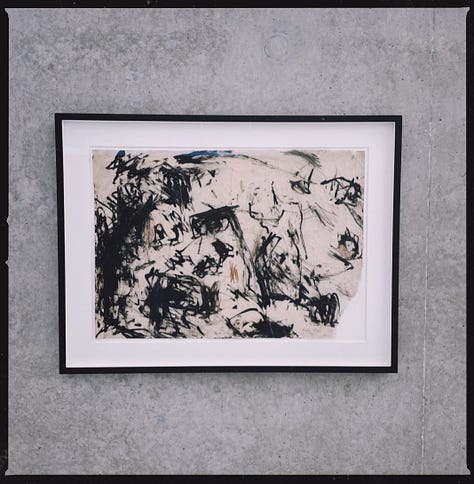

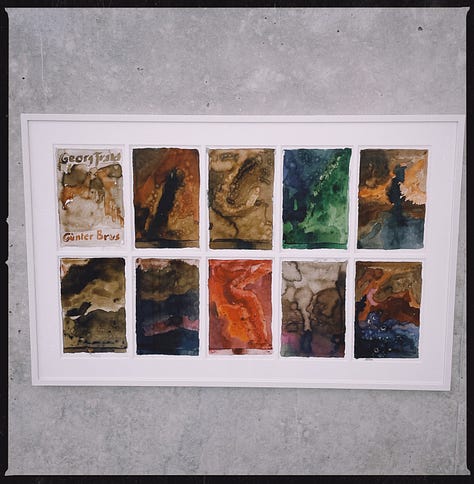

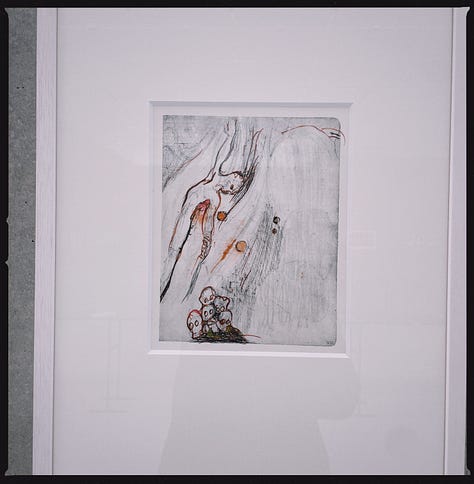

Brus’s paintings and drawings, some of which you can see below, were for me extraordinarily evocative. I know so little about how to talk about painting, and the alembicated lexicon of art writing, that it’s probably best to avoid making any comments on technique, though it’s clear Brus was a technically gifted painter and draftsman. (A video by curator Roman Grabner describing the Bregenz exhibition with English subtitles can be viewed here). I loved Brus’s early drawings which seemed to communicate a profound internalised dread and foreboding, the increasingly chaotic transition of this black mass into black paint smeared across the canvas, the iconic images of the performances with his wife Ana, and his famed ‘Vienna Walk’ where the jagged black brush strokes have seemingly leapt out of canvas and onto his own body, marking a wound for all to see, the self-painter as a living Self-Painting. The final room on the floor was filled with Brus’s dream poems; hundreds of colourful drawings that attest to a rich understanding of the importance of internal images to the process of individuation (and reminiscient of C.G Jung, whose own drawings in his Red Book were not dissimilar to these). I think, in the final analysis, Günter Brus’s artistic legacy will remain important because his life and career were truly authentic.

I came away from that exhibition wanting to write something, but yet not sure what. I couldn’t yet remember the details of my first encounters with Brus, nor was I sure of the personal significance of those images I saw as a younger man. One night I was distractedly scrolling my phone, and it occurred to me that I should probably read a biography in English to understand the basic facts of Brus’s life better. Rather stupidly I ordered the first one I could find on Amazon: ‘More than Just the Canvas: The Art and Legacy of Gunter Brus’ by El Rudolph. When it arrived I could tell immediately from the stunted, repetitive prose that it was AI-generated, and published through Kindle Direct Publishing. The ‘author’ El Rudolph has written other books, all with the same generic, overly descriptive titles and stock images for covers, ranging in subject from German footballer Franz Beckenbaur to musicians like Shane McGowan and the rock DJ Jim Ladd, and countless others all united by the fact that they died relatively recently. The books have no information on the author or the publisher, and seem now to have been taken off Amazon – though the titles are still visible here.

El Rudolph clearly exists in a manner of speaking, but the question remains as to who or what is behind it. Perhaps it is a barely sentient and mendacious artificial intelligence, feasting inattentively on the authentic corpses of the last of these ‘bad’ artists - artlessly regurgitating the bare facts of their lives and affixing an abridged and instrumentalised ‘purpose’ to their art. Perhaps the results are then published, printed and distributed with little to no human contact or input whatsoever. The one thing I have consistently noticed about my infrequent encounters with AI is that it lies brazenly and confidently, and is loathe to admit to its dishonesty unless caught out. Even If the authenticity that those ‘bad’ subjects pursued so relentlessly in their time has had detrimental and unforeseen circumstances in our own, we would do well to remember that without any authenticity and authentic art whatsoever, we will be left with even less than the little we now possess. If we continue along this current path of deferring and delegating the very essence of human endeavour to mediocre machines, our lives and deaths won’t even be of interest to the spectral pen of El Rudolph.