I’ve spent the past five years collecting material in archives, editing, annotating, and writing an afterword for Left Wings Over Europe, a volume of The Collected Works of Wyndham Lewis, finally published by Oxford University Press at the end of February. Lewis was one of the most prolific and significant artists, writers, and intellectuals of English High Modernism. Once described as a ‘one-man Frankfurt School’, his work has fallen by the wayside since he died in the late 50s, no doubt because of his ill-fated political entanglements with, and support for, fascism in the 1930s.

The process of editing was, at times, very difficult and tedious, but it taught me a great deal in retrospect. I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to engage in this type of literary scholarship, essentially an act of faith - one dedicated to the preservation and curation of literary history, and in the service of a future generation of readers that is far from guaranteed. If you’d like to order the book for your University Library or institution, or if you would like to request a review copy, then please do get in touch with me or fill in this form. Below is an essay which takes in some themes explored in this work and Lewis’s other artistic, philosophical and political output from the 1930s. The themes will seem very timely in light of recent events.

Composed hastily and with little foresight as to its potential consequences, Left Wings Over Europe was published in 1936. The book is one of three works of political invective written by Wyndham Lewis against the international order of the western powers, the Soviet Union, and sympathetic towards the fascist regimes in Italy and Nazi Germany. Lewis’s interest in political writing emerged in the aftermath of the First World War, where he had served as an artillery officer and official war artist. He would come to see the war as a completely senseless conflict from which he was lucky to have emerged alive, and one which took the lives of many of his friends. For Lewis, this first technological war portended a new world, one that would be determined by inhuman technologies now capable of transforming the very category of nature.

The eight-mile wide belt of desert across France will be a green, methodic countryside in five years’ time. The harsh dream that the soldier has dreamed - the barbaric nightmare - will be effaced by some sort of cosy sun tinting the edges of decorous lives. At Austerlitz the trees waved pleasantly all through the carnage with Schilleresque oscilliations; the earth at Eylau could not have had many wounds to show […] Ypres and Vimy, on the other hand, were deliberately invented scenes, daily improved on and worked at by up-to-date machines, to stage war. There is, or was, no trace in one of the valleys before Ypres except of this agency.

Motivated by this experience, all of his subsequent non-fictional works were in some sense ‘anti-war’, and Left Wings is no exception - and alongside notable works of the period, it offers a valuable insight into the motivations of an antagonistic modernist writer, artist and thinker of unparalleled originality. For Lewis, any critique of the British liberal establishment’s ‘Left-Wingism’ was inseparable from the cultural establishment’s comparable tendencies, with his longstanding conflict with the writers and artists of Bloomsbury not far from the surface of these accounts. We are also able to witness the decidedly holistic view Lewis had of the world - always viewed through the rubric of aesthetic principles - and the extraordinary breadth of his intellectual interests.

Much like 1931’s Hitler, one of the first English language accounts of the Nazi phenomenon written two years before Hitler’s election in 1933, Lewis’s overwhelming and visceral opposition to war led him to overlook the central elements of the Nazi ideology - its virulent antisemitism and its insatiable appetite for conquest - and to accept at face-value the Nazis’ supposed desire for self-determination and peaceful co-existence. All of these works will leave an indelible mark upon Lewis’s substantial artistic and intellectual legacy—a fact which he himself would acknowledge in his second autobiography, Rude Assignment (1950).

Nevertheless, the experience of writing those political books allowed Lewis to determine the coordinates of his future political thinking, which in the final analysis departed significantly from fascism – as borne out by two works published in 1939 that recounted his previous positions, and later works such as Anglosaxony (1941), and America and Cosmic Man (1946) where Lewis embraces and promotes the post-WWII liberal democratic consensus. Towards the end of his life, afflicted by ill-health and blindness, Lewis would come to embrace the principles of a Catholic universalist theology (though never formally converting). Upon his death, it was discovered that Lewis had an enormous cerebral tumour on his pituatory gland, the suspected cause of his later blindness - but in retrospect perhaps also the cause of a very palpable split personality noted by contemporaries; possessed of an endearingly affable, humourous and helpful nature on the one hand - and a sometimes violent, paranoid and illogically oppositional rage on the other.

Left Wings covers in significant detail the political and diplomatic atmosphere of the mid to late 1930s. It begins by analysing and describing the stratification of British political life in particular and western European democracies in general; the role of mass media in provoking, shaping, and forming public opinion, and the conflicting motivations and interests that were preparing the way for another major conflict. The rapidly shifting role of the press comes in for particular scrutiny. Lewis uses Lord James Bryce’s book Modern Democracies (1921) to analyse how newspapers had begun to possess a degree of political power unmatched through history. Newspapers, Bryce maintained, have not only made democracy possible but are themselves democracy, i.e. an ideological state apparatus that intended to provide only the illusion of discourse and plurality, whilst concealing the true machinations of power - and possessing the ability to sway and form opinion in favour of the powerful.

The overarching impetus for this book came from Lewis’s vigorous opposition to the prospect of another European war. The work was written in response to fast-moving political and diplomatic crises, and though composed and published quickly, events overtook Lewis’s analysis of them. The first half of the decade witnessed the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, Adolf Hitler’s election as Chancellor in 1933, and the gradual disentangling of the various restrictions imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles. Two events in particular provided Lewis with the motivation for writing Left Wings; the Italian invasion of Abyssinia and German remilitarization of the Rhineland.

In supporting Germany’s right to defend its borders and to have unfettered access to one of its most productive industrial regions, Lewis was in accord with many others across the British political establishment and press who had come to regard the Treaty of Versailles as grossly unfair. The main thrust of Lewis’s argument focuses on what he believed to be the reasons behind what was, in his view, a self-defeating British foreign policy; a left-wing orthodoxy that spanned the world of letters, journalism, and politics superficially motivated by an abstract philosophy of ‘uplift’, which ultimately had the goal of making the world ‘safe for communism.’ As D.G Bridson noted, for Lewis, ‘everybody was Left-wing who did not happen to see eye to eye with himself. That which was not avowedly classical was necessarily romantic: all who were not wholeheartedly with him were against him.’[ii]

The scholarship surrounding both Lewis and his close friend and erstwhile collaborator Ezra Pound suffers from a persistent and curious inversion of focus; Lewis’s involvement with fascism tends to be overstated, whereas Pound’s is understated. It is well to note that only the latter materially contributed to the cause of a fascist state and was tried for treason after the Second World War. There are several possible explanations for this curious disparity, but it is sufficient for our purposes to focus on one: with Lewis it is possible to trace the dynamics of his political transformation almost step-by-step. The effect of such an exhaustive intellectual record is subtle but powerful. It provides an unprecedented insight into how a writer and artist, with no recourse to claims of mental incompetence, rationalized a tacit support for one of the most destructive ideologies in modern history.

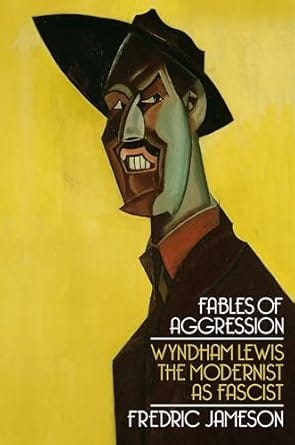

This inevitably creates a discomfort related to the study of fascism in general, one which derives from a tendency to completely mystify the ideology by imbuing it with a certain exceptionalism and aberration free from material, historical, and ideological determination. This tendency obfuscates the fact that for many, Lewis among them, support for fascism was a political commitment primarily motivated by pragmatism. The most salient observation in Fredric Jameson’s noted study Fables of Aggression: Wyndham Lewis, the Modernist as Fascist (1979) is in its description of how Lewis makes ‘himself the impersonal registering apparatus for forces which he means to record, beyond any whitewashing and liberal revisionism, in all of their primal ugliness’.[iv]

Indeed Lewis’s reputation has suffered as much from his belligerent and antagonistic personality as from his ephemeral political opinions. The Lewisian oeuvre in its totality amply demonstrates the difficulties of giving expression to a multifaceted system of thought through an instinctively contrarian and volatile public persona. With its litany of opportunities missed and acrimoniously squandered; patrons, supporters, friends, and lovers insulted and cast aside; its multitude of libel cases and petty squabbles—Lewis’s biography demonstrates how work alone, even work of considerable genius, is insufficient to sustain a legacy in and of itself. One also requires a certain amount of reciprocal goodwill for genius to shine through the miasma of history. Yet Lewis, to his clear detriment, was temperamentally incapable of pandering to a cultural establishment he deemed irremediably dishonest and nepotistic. In Left Wings, Lewis’s belligerence and anti-establishment hostility is at the very forefront, albeit transposed onto the political establishment as an appendage of, and a proxy for, the cultural. In this work, as elsewhere, seemingly straightforward opinions and ideas are, upon closer examination, more intricate than they first appear.

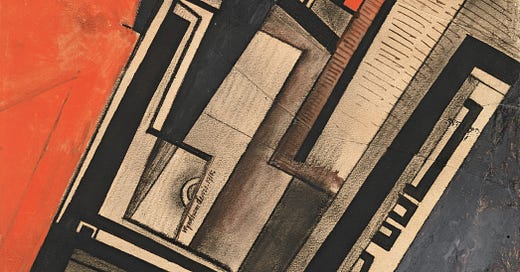

In common with many men of his generation, the war left an indelible psychological impression on Lewis. Before the war, Lewis’s interest in the political was ancillary to his artistic practice and his aesthetic philosophy. As the progenitor and main ideologue behind Vorticism, the principal British avant-garde movement of that period, he was one of very few artistic provocateurs within a decidedly staid and overwhelmingly bourgeois artistic milieu. This privileged and bourgeois bohemian tendency within the British art world was embodied for Lewis by the critic Roger Fry, a member of the Bloomsbury group of artists and writers. After briefly joining Fry’s Omega workshop in 1913, Lewis acrimoniously left after a quarrel over a commission and subsequently set up the Rebel Art Centre with Kate Lechmere in 1914, shortly followed by the publication of the first issue of Blast.

This publication would provide the basis for the Vorticist group, which also included Pound, Edward Wadsworth, Henri Gaudier-Breszka, Helen Saunders, and Jessica Dismorr. The group’s activities, which brought Lewis a great deal of attention and admiration, were cut short by the onset of war. Lewis served as an artillery officer in the trenches for most of 1917, then as an official war artist for the remainder of the war. Some of Lewis’s collaborators and friends, such as Gaudier-Breszka and T. E. Hulme, were killed. In his first autobiography Blasting and Bombardiering, published a year after Left Wings, there are some telling insights into Lewis’s mentality in the post-war years. Recalling his war service, he bitterly recounts how:

The ‘Bloomsburies’ were all doing war-work of ‘National importance’, down in some downy English county, under the wings of powerful pacifist friends; pruning trees, planting gooseberry bushes, and haymaking, doubtless in large sunbonnets. One at least of them, I will not name him, was disgustingly robust. All were of military age. All would have looked well in uniform.

Holding court among fellow artists and conspirators at the Vienna Café on New Oxford Road or at the Eiffel Tower Restaurant on Percy St., Lewis once hoped that they would be the ones to head some future regeneration of European culture. This hope was dashed by the chaos and destruction of war, which brought with it a realization that the sclerotic English class system would always coddle and protect its wealthy elites, even despite their purportedly ‘radical’ and progressive political views. They ‘had money and we hadn’t’, Lewis remarked, ‘ultimately it was to keep them fat and prosperous—or thin and prosperous, which is even worse—that other people were to risk their skins’ (BB: 183). The ‘ambitious and jealous cabal’ of Bloomsbury had made the artistic and literary worlds of England into ‘the afternoon tea-party of a perverse spinster’ (BB: 279). ‘But one cannot choose one’s Government’, Lewis concluded, ‘And we have been governed, in matters of taste, by “Bloomsbury” aesthete-politicians for the two decades and a half that have elapsed since then, especially in the post-war’ (BB: 279).

Such statements are indicative of the profound ressentiment that Lewis held onto long after the war ended. With his promising artistic career interrupted, interest in his work declined significantly, and he often found himself in impecunious circumstances. Conversely, the Bloomsbury group—many of whom already possessed substantial familial wealth—appeared to thrive culturally and materially. Furthermore, it appeared to Lewis as if all of the institutions of the British cultural establishment aided and abetted their cause. Lewis’s suspicion of what he believed was the inherent ‘left-wingism’ of British society can be said to originate partly in his antipathy towards the Bloomsbury set and what he perceived to be their politics. This antipathy was initially aesthetic—as many of Lewis’s opinions were—but soon became ideological. On 3 February 1925, Lewis completed the manuscript for a sprawling and ambitious work he wished to publish as The Man of the World. Rejected for publication in its entirety, it was eventually broken up into separate parts, expanded in places, and published over several years. Among these publications was The Art of Being Ruled, which was published by Chatto & Windus in 1926. For Lewis, its publication signalled the moment when ‘politics began for me in earnest’ (BB: 303).

The abstract political and philosophical thinking advanced by Lewis in The Art of Being Ruled is to some extent removed from the more pragmatic motivations behind Left Wings over Europe. Nevertheless, an understanding of the former is essential to contextualizing the latter. The Art of Being Ruled is a multifaceted work which, in common with some of Lewis’s other non-fictional writing, includes a great deal of lively but mercurial analysis which renders some of his various arguments indeterminate. There is, however, a peculiar logic to this approach. The work is a response to the various destabilizing and alienating forces unleashed by the war. As such, it seems to replicate in form and content the overwhelming multiplicity of this disorientating array of phenomena. In his second autobiography Rude Assignment, published in 1950, Lewis suggests briefly that he intended to utilize the tripartite structure of the Hegelian dialectic, by allowing the ‘thesis’ and ‘antithesis’ to ‘struggle in the reader’s mind for the ascendency and there to find their synthesis’ (RA: 169). Almost immediately, however, Lewis counters that he ‘did not take this very far’ and that any remaining vestiges are a ‘source of occasional embarrassment’ (RA: 169).

Nevertheless the willingness to deploy a philosophical strategy so heavily associated with Marxist political theory demonstrates how far the complex philosophical arguments in The Art of Being Ruled diverge from the hasty and tendentious political analysis of Left Wings over Europe, where the ‘primitivism of the “brave new world” of the Soviets’ is formed of a ‘saurian spinal cord’ provided by the ‘materialist dialectic of Marx’ (p. 5). In The Art of Being Ruled the topics under examination are social, cultural, technological, and libidinal. Lewis addresses the intellectual and philosophical underpinnings of revolutionary movements and socialism, feminism, masculinity, homosexuality as a political subject, the educational system, the decline of the family, and cultural infantilism, among other topics. These analyses are not merely descriptive, however, and throughout, the focus remains on the potential consequences for the individual and how these phenomena exist in relation to governments, power, and the ruling class. The following, again from Blasting and Bombardiering, is a concise appraisal of what Lewis viewed as the book’s main purpose:

The title of this book speaks for itself. I had attacked the problem of government. But it is important to notice that it was advice to ‘the ruled’ that was tendered, not to those who do the ruling. It was instruction for people in the gentle art of keeping the politician at bay. That was what would be called a ‘Leftwing’ book. I’m doing to-day just what I was doing in 1926, when I began. I am trying to save people from being ‘ruled’ too much—from being ‘ruled’ off the face of the earth, as a matter of fact.

It is, of course, absurd to judge works of the past by the standards of the present, and there is much in The Art of Being Ruled that will offend modern sensibilities. Nonetheless, the above description is accurate insofar as The Art of Being Ruled ultimately advocates some form of ‘Leftwing’ socialist redistributive economic programme. The specific details of this programme and its form, however, are noteworthy. Lewis at this point believed in certain forms of racial and national essentialism which diverged from the properly political conception of racial consciousness that would later find expression in the Nazi ideology. Lewis’s thinking on race was conventional for his moment, when culture and tradition were synonymous with a biological understanding of race—and when related neighbouring nations, no matter how close linguistically and physically, tended to constitute themselves as racially distinct. However, it is incredibly difficult to simply dismiss Lewis as a racist - particularly in light of the help and support he gave in the 1950s to the young impoverished Afro-Carribean painter Denis Williams, part of the Windrush generation, on several occasions:

I do not wish to be guilty of what is called overpraising … but I consider Denis Williams a young man of very remarkable talent. He paints pictures the size of a pantechnicon with as little effort as the blackbird sings. But these huge canvases are not the apparently carefree vocalism of a bird, they are heavy with human import … The canvases are big because there is such a volume, such a weight, of emotion there, requiring a big receptacle into which to pour itself …

Lewis sought on several occasions to help Williams out with a job (eventually succeeding in getting him appointed as a teacher at the Central College of Art in London). This was a very difficult task in 1950s England, and before eventually succeeding, Lewis wrote with frustration on one occasion to his friend Herbert Read:

… if he is to survive he must be found a job. Because of colour this presents great difficulties. It is a pity that all this talent should be lost for no better reason than that its possessor’s skin is controversial.

Lewis indeed would later come to view his 1930s views on race as a dead-end and tentively celebrated the potential of the American racial ‘melting-pot’, which he had himself denigrated previously. Lewis believed that as modernity progressed and cultures became more inter-mixed, race would inevitably disappear and cease to be of much importance. Overall, he believed this to be for the best. In this he has been proven to be mostly right - but also mistaken in some sense, for he failed to see how American democracy - deracinated though it is - needed to hold onto a utopian and incoherent conception of a ‘white’ (and ‘black’) race to incentivise the forms of organic solidarity lacking among economic immigrants from heterogeneous (and sometimes openly antagonistic) national cultures, that would otherwise be at odds with each other.

Nevertheless, in The Art of Being Ruled Lewis believed that because of the specific national context and ‘racial’ characteristics of Anglo-Saxon countries, in addition to the structure of their parliamentary democratic system, the type of socialism he favoured was ‘some modified form of fascism’ (ABR: 369) Such a striking statement requires to be understood in context, written as it was in 1926—a mere four years after Mussolini’s bloodless coup of October 1922 following the Fascists’ March on Rome. Lewis’s understanding of fascism was coloured by this event, and the still embryonic and little-understood form of ideology which hadn’t yet been superseded by its more racialist and anti-semitic Nazi iteration. Indeed, Lewis considered Fascism to be a variant of extreme left-wing militancy that had arrived at the same objective as Bolshevism by other means. In the case of Italian Fascism, these means were (via the Futurism of Marinetti) aesthetic:

All Marxian doctrine, all étatism or collectivism, conforms very nearly in practice to the fascist ideal. Fascismo is merely a spectacular marinettian flourish put on to the tail, or, if you like, the head, of marxism. (ABR: 369)

The aesthetic and the ideological were inextricable for Lewis, as they were for many of his contemporaries in the volatile political atmosphere of the 1930s. For Lewis, however, the equivalency of socialism and fascism as he understood them also seemed theoretically consistent when viewed through the work of the French political theorist Georges Sorel, author of Réflexions sur la violence (1908), which was translated into English by Lewis’s friend T. E. Hulme in 1912. Another consistent element in Lewis’s thinking was a tendency to approach politics in terms of personalities, the more interesting, forceful, or compelling of whom tended to spark the most interest.

Lewis’s unyielding interest in the exceptional personality or individual derived from his view of artistic production as a necessarily subjective and solitary pursuit. In the end, the type of political power which Lewis promotes in The Art of Being Ruled is a form of centralized power, which he believed to be the most conducive to individual artistic expression. A decade later, in Left Wings this position is turned on its head—with the centralization of power now representing ‘politically, the greatest evil it is possible to imagine’ (p. xi). The result is the inconsistent and ill-thought-out position advocated throughout the work, which decries the centralization of power through the League of Nations and the increasing ideological and diplomatic confluence of the western allies and the Soviet Union; whilst commending the Hitlerite dictatorship as a bulwark against these processes, ignoring its comparable centralization of dictatorial power.

To further understand how this shifting conception of the political relates to Left Wings, which is a book about political ‘personalities’ as much as it is a book about political events, it will first be necessary to turn to Lewis’s most infamous political work, Hitler. Based on a trip Lewis took to Germany in November 1930, the material originally appeared as a series of articles in the left-wing feminist periodical Time and Tide under the heading ‘Hitlerism: Man and Doctrine’, which were hastily revised and published in book form in March 1931. Lewis’s views, as expressed in Hitler, were influenced by a growing anxiety that political and economic events were leading to another war. Writing amid the Great Depression that followed the Wall Street Crash of 1929, Lewis privately believed (correctly in retrospect) that the economic fallout from this momentous economic catastrophe made war all but inevitable. Lewis considered the prospect of war an emergency, and to this end was prepared to entertain any ideological viewpoint that purported to oppose war—even if this meant accepting a racialist ideology that he believed to be a ‘prejudiced Zoology’:

I do not write this book from choice, for instance: I would far rather, if it rested with me, be engaged in scientific research, or in artistic creation. Ever since in the War, where I served on the Western Front with the Artillery, I was first under fire, there are certain questions I have asked of life which it would have never have occurred to me to ask before . . . .

A state of emergency came to appear for me, as for most soldiers, a permanent thing. Unlike, I daresay, most of my companions, I realized that something in this ‘storm of steel’ required explaining: and the academic meteorology of average public opinion, or of the Press, for these monstrous disturbances, was unsatisfactory. And since that time it is naturally easier to convince me of the imminence of such a condition or of its being a condition inherent in the very nature of our life. (H: 127–9)

The passing reference to Ernst Jünger’s First World War memoir In Stahlgewittern (1922), which posited war as a spiritual experience of the first order, gives us an idea of Lewis’s still ambivalent and unresolved attitude to that conflict. Yet evident also in the above excerpt are the emerging fissures within Lewis’s political thinking, which were clearly in the process of being exacerbated by his visceral opposition to war. Indeed many of the views expressed in Left Wings—for example the various justifications for Nazi antisemitism and some occluded antisemitic sentiments themselves—are in evidence within Hitler. Very early in the work, we are again reminded of how Lewis’s interest in politics is mediated through personalities: in ‘the doctrine of Hitlerism’, he maintains, it ‘is a person rather than a doctrine with which we are dealing’ (H: 31).

In comparison to the cult of personality surrounding Charles Maurras and Action Française, who Lewis now dismisses as ‘amateur’ nationalists, Hitler is said to be an ‘Everyman’, and perhaps most scandalously: a ‘Man of Peace’ (H: 32). However, Lewis’s more fundamental error in this work (and in Left Wings) lies in the assumption that antisemitism is incidental to the Nazi ideology; that it is an inconvenient fact which is peripheral to its more tangible potential advantages, rather than one of its main pathological features. As a result, Lewis rather naively saw within Nazi racialist ideology the potential for western nations to see themselves as kin, and by doing so, to resist all moves towards self-destruction through war and (left-wing or communist) revolution. This view was heavily coloured by a mentality which he himself satirized in his novel The Apes of God, where the literary and artistic worlds are awash with detached and entirely utopian left-wing politics and delusional ideas regarding the working classes espoused by bourgeois fellow travellers of socialism or communism. What is most obvious in Hitler, however, is that Lewis seems completely oblivious to the very same detached and subjective utopianism he himself is projecting onto the Nazi ideology from afar.

The entire text of Hitler is imbued with a certain febrile quality, where we can witness Lewis’s cognitive dissonance in the face of ideas and concepts that require large feats of rationalization and justification. At times, Lewis appears almost unable to accept the views he is himself conveying, yet perseveres nonetheless. Such is the overriding faith he has in his visceral opposition to war, an altogether overwhelming faith in hindsight, which assumes a further level of dissonance in the various analyses of political events put forward in Left Wings. At this point, the question of Bloomsbury and Lewis’s aesthetic and ideological opposition to what he viewed as their hegemony within the British political and cultural landscape returns to the fore.

The working title for Left Wings over Europe was Bourgeois-Bolshevism and World War.[vi] It is a title that brings to mind the bourgeois-bohemians whom Lewis excoriated in his first and most well-known novel Tarr (1918); a depiction intended to represent the Bloomsbury group, among others. It is also worthy of attention that Left Wings was published two years after Lewis’s work of literary criticism Men without Art (1934). In that work, he speculated widely on the aesthetic practices of many of his modernist contemporaries and sought to question the fate of modernism in general and the role of the artist within contemporary society in particular. Of specific interest is Lewis’s essay on one of Bloomsbury’s most prominent writers, Virginia Woolf. We need not dwell too much on the content of this essay, which was negative and dismissive of Woolf’s ‘pretty salon pieces’ and ‘undergraduate imitations’ of Joyce, to understand that a certain ideological antipathy underpins the putatively aesthetic critique, evident in the comment with which Lewis ends the piece:

For fifteen years I have subsisted in this to me suffocating atmosphere. I have felt very much a fish out of water, very alien to all the standards that I saw being built up around me. I have defended myself as best I could against the influences of what I felt to be a tyrannical inverted orthodoxy-in-the-making. (MWA: 114)

The term ‘orthodoxy-in-the making’ is notable here, not only for the extensive use of the word ‘orthodoxy’ in the various descriptions of the political status quo in Left Wings, but also in anticipating to some extent the title of Lewis’s third hastily written political work Count Your Dead: They Are Alive!: or, a New War in the Making (1937). In a review of Men without Art for The Spectator on 19 October 1934, a young Stephen Spender wrote that ‘Twelve well-filled pages of malice and ill-temper—often amusing examples of both—are devoted to attacking Mrs. Woolf’.[vii] Focusing on the above, Spender highlights what he views as Lewis’s persecution complex at the hands of Bloomsbury. ‘This is totally unexpected’, Spender wrote, ‘Why should Mrs. Woolf seem to suffocate Mr. Lewis?’.[viii] This seemed to hit a nerve with Lewis, who wrote a testy letter to the editor in response:

I should indeed be ‘suffocated by Mrs. Woolf’ (to quote from a very muddled sally of Mr. Spender’s)—though in no other sense that I could imagine—were I to be threatened with the policeman should I happen to mention her Lighthouse with disrespect! (Letters: 223)

The suggestion that Woolf’s status as a member of a selective cultural group intimately connected to the political elite implies a connection to the repressive authority of the state, is of course an exaggeration, and surely the product of Lewis’s own paranoia. And yet during this period, so many of Lewis’s works were withdrawn from publication or suppressed due to their libellous content that he did have some cause to suspect a secretive and concerted effort against him. Furthermore, he could not help but conclude that the reasoning behind this effort lay in his political positions and sympathies. ‘That your reviewer is a Communist . . . remains in no doubt’, Lewis wrote in response to another negative review of Men without Art in the Times Literary Supplement on 22 November 1934:

That a member of the Society of Jesus would not be an appropriate person to choose to do a review of a reprint of Darwin’s Works is obvious . . . . But surely a Communist or a Marxist is disqualified in much the same way, for the purposes of ‘literary’ review. (Letters: 226)

It is no mistake then that Lewis begins his contribution to ‘Notes on the Way’, the series of essays that were a prelude to the themes explored in Left Wings and published in Time and Tide where he had serialized Hitler five years before, with a salvo against the politics of the British literary and cultural sphere. A particular emphasis is placed on the ‘intellectuals’ of Bloomsbury:

The world of Letters and of journalism is a ‘Left-Wing’ world. No student of politics can afford only imperfectly to grasp, much less to neglect, that momentous fact. The newspapermen of Fleet Street, as much as the ‘intellectuals’ of Bloomsbury and Hampstead, are ninety per cent. ‘Left-Wing’ in sympathy. All the best advertized ‘authors’ are ‘Left-Wing’ in sympathy. Indeed, it is impossible to be a really well-advertized author unless you are ‘Left-Wing’ in sympathy. You must be a spiritual child of Macaulay—with a mind open on the side of Trotsky, but a mind shuttered on the side of Burke. To write, apparently, in England at this time, is to be ‘Left-Wing’. (p. 163)

There was almost two years between the publication of Men without Art and Left Wings. During this time Lewis suffered from a succession of recurring illnesses that required hospitalization and surgery. Though engaged in the composition of The Revenge for Love, and preparing for a solo exhibition at Leicester galleries, this fallow period was unusually long for a writer as prolific as Lewis and perhaps gives some explanation for the disparity in mediums and subjects—from the abstract speculation of Men without Art (a work of literary criticism) to the journalistic and tendentious prose of Left Wings over Europe. However, this superficial formal discontinuity obscures a certain thematic consistency. If Men without Art intended to take stock of the aesthetic failures of the modernist project and his place within its desultory pantheon, Left Wings over Europe seeks to explore the political consequences of this very failure, which he believed were precipitating another war.

As a result of the harm that Left Wings did to Lewis’s reputation and career, it was clearly not a work which he looked upon favourably in later life. He received ‘practically nothing’ as an advance for these books, and less money than for any other type of book. And yet: ‘I did myself so much damage that at the time it diminished the value of my other books.’ This was no boast, Lewis contends: ‘One does not boast about being a fool.’ It appears then, that Lewis was genuinely contrite in the sense that he had been unwise, and as ever perceptive in noting how these works of hasty and tendentious political invective would, to some extent taint the unique achievements of his otherwise incredibly rich and multifaceted literary and artistic oeuvre, the reult of the lively intelligence of its author. One hopes that it is an oeuvre that will be rediscovered by future scholars, students and artists in the years to come.

[vi] Paul O’Keeffe 2001, p. 358.

[vii] Stephen Spender 1934, p. 576.

This was a fantastic overview, I’ve got to read Tarr one of these days. I’m reading a lot of Pound atm and you’re so right about how he was to some extent given a pass relative to Lewis despite being both much worse and seemingly never really repudiating any of it.

It is quite a treat to learn about a lesser-known member of the modernist movement, especially through the lens of the work that seemed to do the most to ruin his standing. What a tail-twister he was! It's in my nature to appreciate it. After reading, I share your hope that his art and writings find a more prominent place in the canon.