I’d been meaning to write an essay on fatherhood since my son’s first birthday in late summer, but it’s taken much longer than I anticipated. What appears on the surface to be a rather simple theme is full of mystery and misdirection. There seems to be a great deal of counterintuitive advice on the internet concerning fatherhood. Advice, something which everyone on the internet is usually only too willing to provide, is in this regard tellingly circumspect. At its most basic conceptual level, it appears that fatherhood is highly contested, subject to an implicit cultural discourse which proceeds from its fundamentally retrograde character; something to be managed and mitigated - its form, function and purpose are given to be irreconcilable and superfluous to the aims of a putatively progressive society. This was, at first, rather frustrating for those who, like myself, recently became fathers and strive to be worthy of the task. On the other hand, the advice I sought and received from trusted friends was always practical and thus assumed a peculiar character of its own. Despite many of them having also become fathers, in some cases multiple times, there seemed no real way for them to communicate the meaning of fatherhood other than in strictly practical terms. What I have discovered thus far is that fatherhood remains a largely occluded theme, shrouded in a veil of silence; a form of esoteric knowledge that can only be experienced directly. Once experienced, however, one begins to see and feel its uneasy presence everywhere.

In his autobiography Memories, Dreams, Reflections we discover that the most formative aspect of Carl Gustav Jung’s distinctly gothic upbringing was the enigmatic and distant relationship with his father, a protestant minister who died suddenly when Jung was an undergraduate. Shortly before his death, the father purportedly lost his religious faith. The Reverend Paul Jung was an erstwhile student of theology, the thirteenth child of an eminent Professor of Medicine at the University of Basel after whom he would name his only surviving son. He had elected to become a minister due to financial circumstances instead of pursuing an academic career, a decision that caused him a great deal of frustration and unhappiness. Jung would refer to his father disparagingly as ‘reliable but powerless.’ In the vast corpus of Jungian psychoanalytical literature, only a relatively small amount is dedicated to the subject of fatherhood, which stands in stark contrast to the voluminous writings on the protean mother archetype[1]:

[…] the role which falls to the father-imago in our case is an ambiguous one. The threat it represents has a dual aspect: fear of the father may drive the boy out of his identification with the mother, but on the other hand it is possible that this fear will make him cling still more closely to her […] the father archetype is characteristic of the archetype in general: it is capable of diametrically opposite effects and acts on consciousness rather as Yahweh acted towards Job—ambivalently.

- The Father in the Destiny of the Individual (1909)

Jung’s noticeable omissions on the theme of fatherhood suggest a matter of grave import too perilous to approach directly. We need only note that Jung experienced two notable psychological crises which left him significantly changed, both of which were related to the ‘father.’ The first seems to have occurred after an incident when he was twelve years old[2], which led to recurring involuntary fainting attacks. The second occurred in 1913 following his break with Sigmund Freud. Both men openly acknowledged in their letters that their dynamic was one of surrogate Father and Son. Freud wrote knowingly to the younger man, confiding in him his earnest hope that one day he would become his anointed successor:

‘Just rest easy, dear son Alexander, I shall leave you more to conquer than I myself have managed.’

Louis Althusser posited that Freud, in creating a new discipline and a tangible scientific method to approach the realm of the unconscious, was forced to become ‘his own father.’ In the case of Jung, he was compelled to initially follow the lead of this father, before departing from the constraints of his benevolent guidance so that he may forge his individual path. The surrogate paternal-filial conflict is often no less potent than the actual, characterised by a need to question, undermine and surpass that inevitably leads to some measure of rupture. Amid their breach, Jung thought himself on the verge of psychosis and experienced prophetic visions of an impending cataclysm about to engulf the world, vindicated shortly after by the outbreak of The Great War. It was during this crisis that Jung began to work on his magnum opus, The Red Book, an account of his return from a state of spiritual alienation and crisis through rediscovering the image of God within the disparate symbols of his individual cosmology, and placing it in dialogue with the suppressed wisdom of the ‘collective unconscious.’ The book stands testament to the power of aesthetic sublimation and creativity, but we cannot fail to note that within this reconciliation with First Principles, this re-engagement with the fundamental signifier, there is also a deeper recognition and understanding of the unhappy fate of his own father, and ultimately a rediscovery of the faith once lost to both men. Although I had distractedly read Jung when I was younger, an abiding interest in his work was awakened only relatively recently by a set of synchronicities that occurred when we lived in Japan, perhaps a year before the arrival of my son. After our return to Europe, he ended up being born in Bregenz on Lake Constance, in the region where his mother was also born - some 50 miles along the coast from where Jung himself was born in Kesswil.

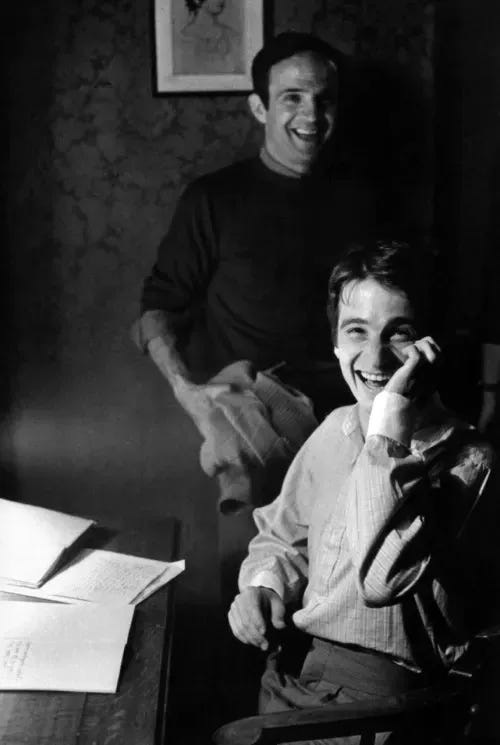

When I decided to embark on this essay, for reasons that would eventually become clear, Francois Truffaut’s 400 Blows was frequently on my mind. We had just got back from a short holiday in Paris, the first time I’d been back in over a decade, so it is quite likely that my reawakened Francophile tendencies had some influence. It’s one of those universally beloved films that few can argue is undeserving of its acclaim. A poignant and deeply humanistic autobiographical portrait of boyhood and adolescence, 400 Blows allows the audience to inhabit the diminutive and muddled perspective of the misunderstood rebellious child; to see through his eyes, all of the banal cruelties and injustices that the adult world often inflicts on children. What I admire most about Truffaut was that he was an autodidact (his ‘education’ consisted of watching three films, and reading three books, a week) who was fortunate enough to benefit from the paternal benevolence and mentorship of older men such as André Bazin, co-founder of Cahiers du Cinéma. Bazin died of cancer a day after filming for 400 Blows commenced, and it is to him that the film is dedicated. It was Bazin’s influence that saved Truffaut from a life of delinquency and crime that may eventually have led to imprisonment and perhaps even an early death. Truffaut described Bazin as ‘a sort of saint in a velvet cap living in complete purity in a world that became pure from contact with him.’

In the small downstairs study of our old house, built by my wife’s grandfather, there is an abstract linear painting of a horse and carriage; playful, formally interesting, and evocative. It was gifted to him by a stranger, an artist, who turned up at his door out of the blue one day when he was already well into middle age. He had pulled this badly wounded young man to safety out of a bombed-out trench during the fall of Berlin; both of them were teenage conscripts manning the last artillery guns of the Wehrmacht against the advancing Red Army. Saving another man’s life is a debt that is perhaps impossible to repay in this world, but the life one goes on to live can serve as some measure of spiritual restitution. I can’t pretend to be acquainted with the minutiae of Truffaut’s personal life, but even if one takes this affecting and beautiful film (his first), not to mention a lifetime’s worth of remarkable work, we may assume that Truffaut succeeded in proving that his life was indeed worth saving. It was not surprising to me to learn that 400 Blows was released the year that Truffaut also became a father, and also to learn of the guidance and support he gave to his untutored young lead actor Jean-Pierre Léaud, also a rebellious and disruptive child from a difficult family background in whom he sensed some commonality. Léaud would go on to collaborate with Truffaut on many films and became a prominent actor in his own right. Much like Jung, Truffaut well understood that those unfortunate enough to lack an adequate father can and should seek them out wherever they can find them, and also should not hesitate to step into the role when required.

In thinking about fatherhood I’ve inevitably been thinking about my childhood, which was also characterised by boredom and delinquency until I discovered and became interested in certain things of my own accord. Despite the credentials I have accrued over time, much like Truffaut, I consider myself to be an autodidact, though unlike him I was never a diligent reader growing up. I never read anything independently other than what was set in the classroom until I was about 14 years old. Up until that point, I had a healthy contempt for books and readers – and school in general - much preferring sports, music, games, vandalism and occasional truancy. When I finally discovered reading I embarked on an idiosyncratic journey through different literary traditions which has lasted to this day. Despite the demand for structured thought and learning inculcated by many years of studying and working in universities, my manner of thought and writing remains more influenced by my initial temperament. I remember only vaguely the things I grudgingly learned by rote to easily pass exams, but I still regard myself as an autodidact because the things I still retain were those that I discovered independently. I doubt that I will ever find the classroom dynamic to be anything other than uncanny, particularly now that I occupy the position of authority - but until the birth of my son, I was fortunate enough not to have given it too much thought. I recall now that much of my upbringing consisted of being compelled to learn assumptions and precepts only to eventually discover that they often did not cohere with the way of the world. Most of my poignant memories of childhood are imbued with this dual process of enchantment and disenchantment. Yet the only lesson I’ve drawn from this experience, and which I hope to impart to my son one day, is to never stop attempting to seek out novelty and enchantment despite its ephemeral nature and the inevitability of its opposite.

One afternoon three days before my son was born, my wife sent me off to the supermarket to buy some things we urgently needed. Not yet ready to abandon a lifetime’s worth of reckless and stupid behaviour I cycled back quickly and distractedly without a helmet, a shopping bag hanging precariously on each side of my racing bike. One of the bags caught in the spokes of my front wheel, throwing me over the handlebars at high speed. Fortunately I had the wherewithal to break my fall with my wrists, only bumping my head slightly. Both wrists were badly sprained and cut up, and as I result I was unable to pick up and hold my newborn son without assistance for the first three weeks of his life, and I was paranoid about exposing him to germs from my bandaged cuts every time I did. This inauspicious start to our relationship made me acutely aware of the primary physiological instinct which his presence instilled in me from the very outset. This is a heightened awareness of the dangers that surround him, and a need to always try to protect him by any means possible until he has learned how to protect himself. As he gets older, I’ve started to discover that this desire to protect often goes against his already strong adventurous spirit, his curiosity and mildly stubborn will. My biggest fear now is that I will fail in my role as protector, or some accident will prevent me from performing my role. I also cannot seem to shake the feeling that a single angry word, raised voice or harsh tone will become encoded within the mind of my son, thereby having some adverse effect on his personality. I can only speak for my instincts, which tell me that harsh words are perhaps more easily forgotten, but a lapse in paternal protection is hard to overcome or forget and that it is necessary to always be vigilant.

My autodidact reading habits took me in some strange aleatory directions, from Sherlock Holmes, Jack London, and H.G Wells to Russian literature, which I read through with more systematic diligence than anything I’ve ever attempted. Despite having no knowledge of the historical context or its meaning, I was immediately mesmerized by the sullen philosophies of the ‘superfluous man’ and the ‘nihilist.’ To my mind, the most memorable depiction of the latter was Yevgeny Bazarov from Ivan Turgenev’s sentimental novel Fathers and Sons (1862), which I read as a 16-year-old. Bazarov is the type of romantic anti-hero immediately appealing to the teenage boy; a scientist, a would-be revolutionary, arrogant and brilliant, contemptuous of authority but loyal to his friends: a courageous but ultimately tragic figure. My initial affection for Bazarov has not exactly diminished, but it has undergone a certain change. Turgenev depicted perfectly the generational conflict of Russia in the 1860s; the transmutation of the ‘superfluous man’ – the brilliant but disconsolate poetic hero at odds with the vast archaic cruelties and injustices of feudal Russia – into a new emerging radical type. In Bazarov, Turgenev attempts to present to us the cold, hard, rational positivist who wishes to ‘clear the ground’ for revolution, who disdains all the petty consolations that the previous generation holds dear; art, poetry, nature and romantic love. It was a prescient depiction that would, to a certain extent, approximate the course of Russian history up until the revolution and in its aftermath. Yet what strikes me now is the kindly benevolence of the ‘fathers’ within this novel, their genuine admiration for their sons and their aspirations to be better men than themselves.

When in the end Bazarov is on his deathbed, struck down by typhus, he requests to see the woman he has fallen in love with and who rejected him – overpowered by the very sentiments he had tried so hard to repudiate. ‘Love turns out to be something more than man’s biological pastime’, Vladimir Nabokov noted in his lecture on the novel. ‘The romantic fire that suddenly envelops his soul shocks him; but it satisfies the requirements of true art, since it stresses in Bazarov the logic of universal youth.’ Before Bazarov dies he falls unconscious, having agreed to take the last rites at the behest of his devout old father:

When they were anointing him and the holy oil touched his breast one of his eyes opened, and it seemed as though, at the sight of the priest in his vestments, the smoking censer, and the candle burning before the ikon, something like a shudder of horror passed over the death-stricken face. And when he finally breathed his last sigh and the house was filled with general lamentations Vassily Ivanych was seized by a sudden frenzy. ‘I said I would rebel,’ he shouted hoarsely, his face inflamed and distorted, waving his clenched fist in the air as though threatening someone – ‘And I will rebel, I will!’

This outburst from Bazarov’s devoted father, a retired army doctor, remains for me one the most enigmatic scenes in Russian Literature. The father attending to the death of his rebellious son who did not ‘bow down before any authority, who does not accept any principle on faith’ impotently declares that he too now will ‘rebel’, before being comforted by his distraught wife. What does he intend to rebel against? I was always made to understand that the father is the arbiter of the Law, in lieu of its ultimate guarantor. His function – we are given to understand – is emphatically not to rebel. Yet every father was also once a son.

In an otherwise detailed lecture, Nabokov left this particular passage of Fathers and Sons unremarked. In 1922 Nabokov’s liberal politician father, V.D Nabokov, was fatally shot by Pyotr Shabelsky-Bork and Sergei Tarboritsky, members of the Chornaya Sotnya Russian fascist movement, as he shielded his political rival Pavel Milyukov during a public debate in Berlin. The younger Nabokov was in his early twenties and recently graduated from Cambridge. As the mannered reveries of his magisterial autobiography Speak, Memory reveals, the circumstances surrounding the untimely death of his father would indelibly mark the young writer, and colour the texture of his prose and political thought. Nabokov seemingly loved and admired his father in an uncomplicated manner, perhaps because he was taken away from him when he was rather young, and because he died a hero. In a similar vein Joseph Conrad’s idealist father the poet and playwright Konrad Korzeniowski, played an active role in the Polish uprising against Russian rule in 1861 for which he was imprisoned and sent into exile. The inhospitable climate of exile caused the death of his wife by tuberculosis in 1865, the same illness that caused his own four years later, orphaning their 12-year-old son. If we are to go by the complex portrayals of revolutionary idealism and its corruption in his many works, we can see that Conrad’s view of his rebellious patrimony was somewhat more ambiguous. Conrad’s rebellion was to a certain extent against the precise manner of rebelliousness pursued by his father, but it cannot be said to be a complete negation.

My father could also have suffered the tragic fate of hapless idealists, but with luck did not. Instead has been made to suffer the impertinent and irrational resentment of his son in old age. I regret that I still can only admire my father at a distance. He has suffered two strokes in the past few years and is now in the midst of cognitive decline. Instead of eliciting sympathy, and against all logic and better judgment, I find myself unable to be anything other than impatient or angry in his presence. My father wasn’t absent but he always seemed to be preoccupied – busy working aimlessly and without much reward in a cold foreign country, trying to make up for something, or to recapture it; a loss of prestige, status, honour and other such abstract notions that seemingly mattered more to him than material circumstances. Having achieved success early in life, he succumbed to the hubris of ‘luxury beliefs’, but soon discovered that sticking to vaunted principles was anathema to the type of success that had come to him so easily before, that systems upheld by lies and corruption care little for those who wish to stand up for truth, and will do all it can to punish and destroy those who don’t uphold the venal status quo. However, it was ultimately his failures that I resented rather than the nature of his endeavours. Had he been successful in proving the sanctity of those abstract principles, my admiration may have been more uncomplicated. He had something to prove to himself over and above everyone else, which I can now grudgingly appreciate, seeing something similar in the life choices that I believed so stubbornly, and for so long, to be antithetical to his. If there is some modicum of respect, however, there is also a desire not to replicate that particular drive, which scarcely manages to conceal its conceited origins.

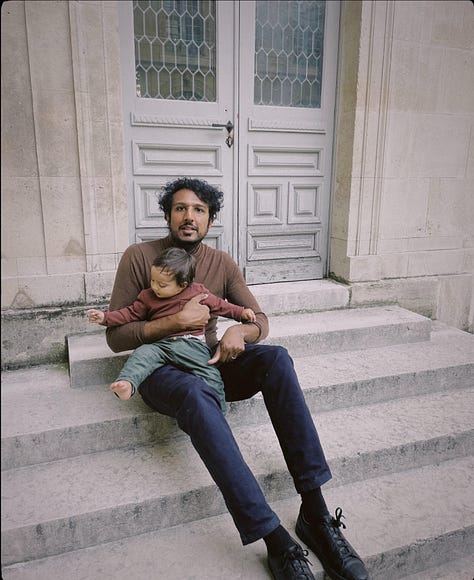

Shortly after my son was born my father asked if I would baptise him, which we eventually did this summer – something which amid my youthful rebellion I could never have countenanced, but which now makes perfect sense. I understand that much of my irrational frustration is spurred by a change in our dynamic. Where previously there was the perpetual antagonism often caused by comparable temperaments, the back and forth between worthy adversaries - there is now on one side only a man of greatly diminished capacity, an object of pity. In the words of Giorgio Viola, the humane old revolutionary of Conrad’s Nostromo, whose own son died in infancy, and who is tragically fated in his senility to mistakenly slay his surrogate: ‘Life lasts too long sometimes.’ The best a father can hope for is to remain frozen in amber as a figure of uncomplicated devotion and admiration by the infant child, before they grow, mature and eventually become disenchanted with the realities of the father’s existence; his weaknesses, his faults, his overbearing authority or lack of it - his inevitable decline. Perhaps the fate of all fathers who live long enough is to eventually recede into the background, to be pitied and forgotten by their sons, at best. The thought that I too will become such a figure for my son, who at this point barely stands to a height of 85 cm, can say all of 10 words, and is enthusiastic about balls, cars, and pointing out dogs, is a difficult one to bear. And yet my instinct is that I should be resigned to the inevitability of this occurring, if only for the fact that the son’s birth has already marked him as the successor and superior to the Father in every possible way, that he has already surpassed him.

Despite the ambivalence and all of the difficulties that the task itself brings, I cannot help but feel profoundly optimistic as a father. I now understand that all of my previous fears and anxieties merely underlined the fact that being a father is the only consistent ambition that I have seriously held and that I have unconsciously considered everything else as preparation for it. When you have resolved to live it becomes your duty not merely to survive, but to live fully, and to ensure that life not only continues - but that it may persevere and thrive beyond your meagre quantity of years. For me becoming a father has been to immediately acquire a tangible stake in humanity, and thus to genuinely wish not only for its continued existence but to fervently hope for the eradication of all injustices that threaten it. I feel immeasurably grateful to have discovered that the secret to alienation from life is not to retreat, but to embrace it fully, in all of its absurd inequities, its subtle synchronicities; to not withdraw into the solipsistic desire to only better know oneself but to come to the realisation that any such quest is doomed to failure, since true knowledge of the self is impossible unless considered alongside its relation to others.

A few years ago when we first began to think of having a child, and not quite knowing the long and difficult path ahead, I re-read The Count of Monte Cristo. Shortly before he was born I bought my son a copy…in the hope that he would one day read its ending:

you must needs have wished to die, to know how good it is to live […] all human wisdom is contained in these two words: ‘wait’ and ‘hope’

For Arno

[1] It seems necessary to note that my direct encounter with motherhood has left me in an inexpressible state of awe which I feel neither qualified nor willing to fully articulate.

[2] Jung, as he confessed in a letter to Sigmund Freud, was sexually abused by a man whom he once admired. Some scholars have speculated that this possibly occurred when he was 12 years old, that the perpetrator was a man acquainted with his father, possibly also a member of the clergy, and that his father was completely unaware of the incident. An interesting and ambiguous counterpoint to this dynamic is a fictional incident in Celine’s Death on Credit (1936). The young autobiographical protagonist Ferdinand Bardamu, at eleven years old, is delivering antiques with his father from their family shop. He is coaxed into the bedroom of a wealthy older woman customer, on the pretext of helping her with something. She proceeds to sexually assault him by undressing and making him look at her genitals, while his father waits in the living room, seemingly oblivious to what is occurring. Afterwards, the woman gives the father a large tip. On their walk home, Bardamu’s brutal and violent father is tearful and markedly more affectionate towards him than he’s ever been before.