*A version of this article appears in print in the arts and culture magazine The Toerag, Issue 6, Summer 2025, ARTEFACTS. You can buy a copy here. Many thanks to editor Rachel Dastgir for her input.

To some extent, this is a companion piece to an earlier essay I wrote called ‘Divine Violence and the End of Pain’ in April for The Mars Review of Books ‘, which is now de-paywalled.

The most rabidly decadent origins of this new theory of war are emblazoned on their foreheads: it is nothing other than an uninhibited translation of the principles of I'art pour l'art to war

- Walter Benjamin

The epilogue to Walter Benjamin’s most famous essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935) alludes to the aestheticisation of politics as a signal characteristic of fascism. Though not made explicit in this piece, one of his principal targets of criticism was Ernst Jünger, the leading light of the German Conservative Revolution, and for Benjamin a writer who embodied the ‘depraved mysticism’ at the heart of German Fascism. He saw within Junger’s exaltation of war as a spiritual experience of the highest order, remnants of the bourgeois aesthetic tendency of I'art pour l'art, which he vehemently opposed. Yet Benjamin was wrong in his appraisal of Jünger, as he was in much else. And it is clear that Benjamin’s antipathy partly derived from an unacknowledged commonality that transcended political affiliations and loyalties. Both men expressed a fascination with the potency and efficacy of ‘divine violence’ as a revolutionary principle, and were obsessed with how technology might hasten or hinder such a revolution. We find in Jünger’s philosophical writings from the 1930s the same ambivalence towards technological society expressed by Benjamin. In his essay On Pain (1934), Jünger’s insights into the nature of technological anomie in his time sound a prophetic forewarning to the present. The photograph, according to Jünger,

…stands outside of the zone of sensitivity. It has a telescopic quality; one can tell that the event photographed is seen by an insensitive and invulnerable eye. It records the bullet in mid-flight just as easily as it captures a man at the moment an explosion tears him apart.’

The emerging power of technology was for Jünger embodied in the unreality inculcated by the dominance of the photographic image, which functions as an ‘expression of our peculiarly cruel way of seeing… a kind of evil eye, a type of magical possession.’ These insights were informed by his experience in the First World War, the first truly technological war, and one which exterminated almost an entire generation of young men, leaving countless others with both physical and psychological afflictions. As one of the twentieth century’s most faithful disciples of Nietzsche, Jünger actively sought out the conflict and was highly decorated for his service, which provided inspiration for his memoir Storm of Steel (1920). Writing in 1934, he proposed that the coming decades would be determined by men who, having survived the turmoil of that war, could gain spiritual insight and mastery over the physical and psychological ‘pain’ that was its inheritance:

Wherever values can no longer hold their ground, the movement toward pain endures as an astonishing sign of the times; it betrays the negative mark of a metaphysical structure. […] The amount of pain we can endure increases with the progressive objectification of life. It almost seems as if man seeks to create a space where pain can be regarded as an illusion, but in a radically new way.

Jünger portrayed the First World War not as a societal aberration, but as instructive of what was to come out of an increasingly technological society, and it was this analysis that made his writings unique. Yet such arguments were merely speculative, diagnostic as opposed to prescriptive, as his subsequent political trajectory and resistance to Nazism should attest. If a new society was to emerge from the destruction of the First World War, it would require a new type of man. This man should be suited to a future that, through the intervention of technology will become increasingly disembodied, causing him to drift further and further away from the ‘Zone of Sensitivity.’ Jünger would later come to acknowledge after the second catastrophic war of the twentieth century, that it is precisely such disembodied insensitivity which hastens the descent into depravity and moral turpitude.

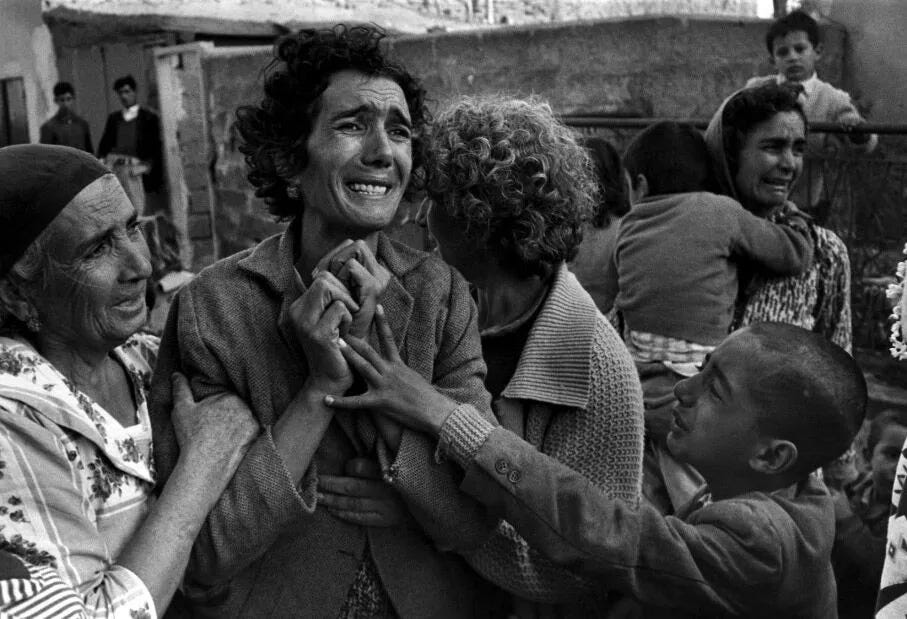

In the 2012 documentary McCullin, the war photographer Don McCullin provides a moving description of his underlying philosophy, one which set him apart from the obscene and macabre voyeurism that attaches to the field. Unlike Robert Capa, McCullin’s work rarely betrayed a romanticised fascination with war – and it resisted the somewhat academic didacticism of James Nachtwey. McCullin’s first assignment was to cover the brutal civil war between the Greek and Turkish communities in Cyprus, where he witnessed many atrocities. He entered one house where all of the men in the family had been murdered mere hours before; the bodies had yet to the cleared away, and the blood had been warmed by the midday sun. The women and children of the family were still present, stricken with grief and despair. Among all this chaos and unfathomable misery, he discovered an unexpected dynamic, a silent accord between photographer and subject. Those family members still permitted him to take pictures – often through wordless gestures, sensing the importance of his role as a witness to this atrocity. He noticed too, the first stirrings of a consistent leitmotiv amidst the Goya-esque horror of war – scenes that were captured not in retrospect through some mannered artistic rendering onto the canvas, but in the very moment they occurred.

He would take some of his most iconic images by dropping to his knees, such as the photograph of a woman learning that her husband had been murdered. In moments of such raw, debilitating grief and pain, McCullin noted that people always looked up to the heavens, involuntarily pleading. It was also in Cyprus that he came across a village being evacuated by British peacekeeping forces before an attack, and witnessed a soldier attempting to move along an elderly woman so infirm she had two walking sticks. After taking a single photo, he lay down his camera, picked up the woman, light as a bag of bones, and carried her to safety. Despite the inherent cruelty of the medium in which he worked, McCullin decided that his philosophy was to always be on the side of humanity, of life against death; that his job was not to shun pain, not to see it as merely illusory, but to confront it head-on.

McCullin claimed to be neither a poet nor an artist. Yet his former editor at The Sunday Times remarked that from the first published photos one could already tell that his most valuable asset was a ‘sensitivity,’ a genuine sense of empathy that is impossible to fake. Those photos were of a Teddy boy street gang known as ‘The Guv’nors’, implicated in the murder of a policeman. He had grown up around them in Finsbury Park, and he was able to hold his own in that impoverished, unforgiving and violent environment. As a child he had wanted to be a painter and received a junior arts scholarship to study at a local college, but since his father died when he was fourteen, he was compelled to work. During his national service with the RAF, he learned photography and bought a camera. Though barely able to read due to dyslexia, and lacking much formal education, he was able to nurture his artistic talent through determination. He understood early, and instinctively, that a sensitivity is of paramount importance to any worthwhile artist – and that it ought to be attached to some form of principle beyond oneself, however abstract – which will then serve as a defence against the cruelty and brutality of the world.

McCullin recalled not only the most memorable photos he took, some of which have become the most famous images of war in modern history – but also the ones that he did not. Witnessing a summary execution of a suspected Viet Cong insurgent by a policeman with a handgun on the streets of Saigon, surrounded members of the foreign press corps snapping photos gleefully – he recalled being the only one among them to put his camera down, not wishing to bear witness to a murder. The title given to a collection of his photographs was Hearts of Darkness (1980). The reference to Conrad’s famed novella at first seems rather apt, but on further reflection seems incongruous. What partially redeems that nightmarish tale is the ‘infinite pity’ of Marlowe, which spurs him in the end to protect Kurtz’s betrothed from the painful knowledge of that man’s true depravity. It is a concession to the importance of illusions. Yet the very specific talents of Don McCullin (the confrontation with pain, the necessity of shattering of illusions) stand in stark contrast to the ‘universal’ genius of the malevolent Mr Kurtz. Also driven out to seek his fortune by his ‘comparative poverty’, exposed to enough sordid brutality to drive most men mad, McCullin was able to persevere through loyalty to a simple principle – one that did not require the veneer of eloquence to disguise a fundamental deficiency - or to deflect from the abysmal hollowness at its very core.

McCullin’s personal ethos was inevitably imperfect. He was, by his own admission, addicted to conflict, to putting his life on the line with no good reason and for modest rewards. Like many men before and since, it’s likely that his fine moral sentiments, no doubt genuinely held, obscured that unconscious, irrational masculine drive which often seeks the affirmation of life through proximity to death. He also deliberately strived for objectivity to placate the media gatekeepers of his time, a habit which made his later canonisation into the British establishment quite seamless. Doubtless this was a necessary strategy, one familiar to all working-class upstarts who attempt to transcend the sclerotic class boundaries of Britain. Nevertheless, he believed that if he allowed his work to be political, it would suffer as a result. However, in disavowing the overtly political and self-consciously didactic, by allowing his empathy and sensitivity to lead his work, like all good artists, he was able to stake some claim to the vital domain of moral right.

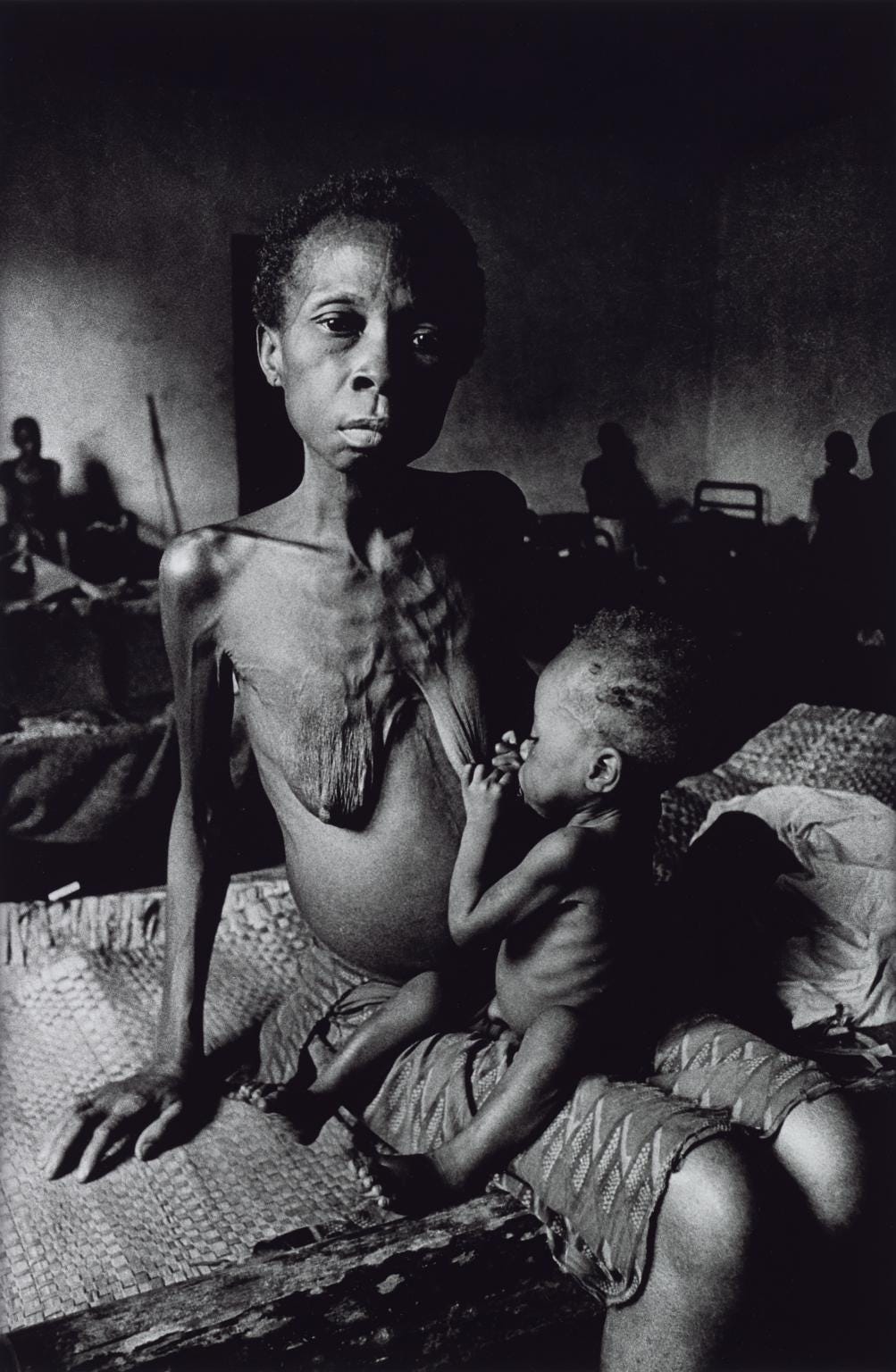

With the advent of social media and the overwhelming proliferation of images depicting war, suffering and death, the opportunity for expressing a ‘sensitivity’ has almost completely vanished. In 1969, the outrage caused by McCullin’s images of the children caught up in famine amidst the Civil War in Biafra, a conflict that was a legacy of the British Empire and Britain’s postcolonial rear-guard policies, had a galvanising political effect on people around the world. As McCullin noted, he wasn’t entirely sure what he intended his photos to convey ‘except, perhaps, that I wanted to break the hearts and spirits of secure people.’ In the present moment, high-definition images of atrocities are beamed directly to our phones of children in Gaza being bombed, maimed, burned alive and slaughtered with impunity by a rogue ethno-state, which acts not only with the tacit approval of the West, but also with its material support. Yet such images have failed to instil any comparable sense of moral outrage. The most generous explanation is to attribute to this indifference some form of collective fatigue; powerlessness in the face of democratic societies where normative expressions of outrage have negligible efficacy. This explanation deflects from another, which addresses a marked shift in our relation to the aesthetic effect of images of war, and to the very notion of the aesthetic in itself.

I have a friend, more than a decade older than myself, who once wrote for Vice magazine at its inception. I have the feeling that his worldview was highly representative of his generation, and the publication he once wrote for. He had an unshakeable ironic detachment; a purposeful lack of passion towards anything and everything. A highly intelligent man, he affected a deliberate air of anti-intellectualism, of studied ignorance worn as a virtue. His principles, possible to discern only vaguely, seemed to be defined by his faith in a decontextualised notion of counterculture; a vague commitment to an expansive idea of freedom; of speech, expression, thought, assembly, markets. He loved expensive and obscure streetwear brands, Fred Perry polo-shirts, sneakers, the idea of football hooliganism, a lover of ‘street-art’, up-market casual dining restaurants. He was militantly individualistic and politically ‘libertarian.’ What irked him most were ideological grand narratives, particularly those of the left. Underpinning his worldview were two contradictory beliefs. The first was in the irremediable corruption of the political and the capitalist ownership classes. The second was an unshakeable faith in their preferred forms of governance and economic policies. He purported to take nothing seriously, yet his whole being seemed to yearn for something that could command his respect. Vice Magazine was the pre-eminent publication of an erstwhile recuperated counterculture that became mainstream culture. The worldview of Vice is thus imbued with an additional layer of infantile resentment towards that same culture – the culture of the boomer parents. It was a simultaneous faith in the aesthetic value of counterculture, and a rejection of the conditions of hyper-politicisation that produced it. When this peculiar worldview was applied to the field of conflict reporting and images of war, something disturbing began to emerge.

Vice’s conflict documentaries were inspired by the gonzo journalism of a bygone era; ironic detachment was its default mode, as was the rejection of moralising and judgment. Yet it also foregrounded the aesthetic touchstones and leitmotivs most beloved by its audience amid the more prosaic and dull horrors of war and destruction as reported by the mainstream media. Much like the tabloid journalists' preference for plain-speaking and common-sense values against the abstractions of the hated intelligentsia, this new type of conflict journalism sought to make its appeal primarily through a shared sense of the aesthetic and an instinctively ironic – though nonetheless sincere – valorising of the cultural artefact over the human subject.

Despite its superficial emphasis on the aesthetic, the result is not the universal sensitivity championed by photographers like Don McCullin, but rather a form of spectacular and strangely neutral fascination that borders on perversion. The ‘aesthetic’ in this case is far removed from its Kantian associations and is better expressed by what I, and art historian Christos Asomatos, have termed the Ideological Aesthetic. The term describes a state of culture, driven by the alienating forces of technological anomie, where the ideological and the aesthetic become conflated, becoming mutually constitutive and dialectically related. The conditions which produce it are themselves paradoxical: a social field over-saturated by technology and prey to a cumulative hyper-politicisation that eventually results in de-politicisation. Signs of this tendency are everywhere in the contemporary digital culture, evident in the increasingly muddied everyday lexicon of young people for whom the very term ‘aesthetic’ is both noun and adjective. Here, the Ideological Aesthetic shapes the conditions in which the rebel of a recuperated counter-culture thrives. The rebel is the product of an institutionalised oppositionality, whose putative antagonism legitimises the conditions of his freedom, while continually rendering that freedom impotent and inconsequential.

The recent generation of modern conflict reporting platforms on social media that have come in the wake of Vice continue its hackneyed pseudo-gonzo style, but they more fully embrace the denatured forms of the Ideological Aesthetic. This new approach to conflict reporting betrays an even more untethered lust for spectacle, one which delights in the capacity to shock but remains indifferent to the purpose of shocking. There exists an unabashedly fetishistic and almost pornographic relation to the violence of the conflicts covered, which invariably reduce conditions of human suffering to the status of an apathetic spectacle, confirming the viewer’s suspicions of the inherent corruption of the world and his insulation from it. The spectators are mostly young men, conditioned to look to these images merely for confirmation of an already bleak and cynical worldview, provided to them without any account of material conditions and causes, free from judgement, or any semblance of moralising. What is left to the spectator is merely the injunction to observe at a distance, as morbid entertainment. This crude form of ‘war photography’ is eminently worthy of the conceited bourgeois principles that Benjamin abhorred in the ideology of Art for Art’s sake. It was, however, a connection he was unable to identify in his own blind faith in the revolutionary potential of technology and the power of cinema. Theodor Adorno, who read an early draft of Benjamin’s famous essay, immediately saw this lapse:

“The laughter of the audience at a cinema…is anything but good and revolutionary; instead, it is full of the worst bourgeois sadism.”

The difference between the black and white photography of Don McCullin and the high-definition video and stylised fashion images produced by what I refer to as the New War Photography is clear on the level of formal qualities. Less obvious is the yawning chasm that exists between the palpable sensitivity of the former, and the complete absence of the same in the latter. If McCullin’s was a refusal of an overt didacticism, it imparted lessons nonetheless. At the most visceral level, he inflicted the pain of his subjects upon the viewer. In contrast, the New War Photography has succeeded in accordance with Ernst Jünger’s prediction. Encouraged by the unprecedented objectification of quotidian life by technology, and by way of the Ideological Aesthetic, it has created a nominally radical new space of insensitivity that thrives amidst the blurred distinction between virtuality and actuality. In this new disembodied space, pain can indeed be regarded as an illusion – even as a perversely edifying and gratuitous spectacle. Contra Jünger, this is not in any way a harbinger of revolutionary dynamism but rather of entropy and dissolution. Breaking free of its spell will require us to reject our cruel fascination with the image, and reacquaint ourselves with the humanity that lies behind it.

Brilliant text Udith, thanks a lot. I clicked on the link you provided on ideological aesthetics and it gave me an error. Could you please pass it on over here? I am very interested.

On the other hand, this piece reminded me of this.

https://www.davidshields.com/books/war-is-beautiful

Brilliant piece. Thank you.